Deep Dynamics Models for Dexterous Manipulation

–>

Figure 1: Our approach (PDDM) can efficiently and effectively learn complex

dexterous manipulation skills in both simulation and the real world. Here, the

learned model is able to control the 24-DoF Shadow Hand to rotate two

free-floating Baoding balls in the palm, using just 4 hours of real-world data

with no prior knowledge/assumptions of system or environment dynamics.

Dexterous manipulation with multi-fingered hands is a grand challenge in

robotics: the versatility of the human hand is as yet unrivaled by the

capabilities of robotic systems, and bridging this gap will enable more general

and capable robots. Although some real-world tasks (like picking up a

television remote or a screwdriver) can be accomplished with simple parallel

jaw grippers, there are countless tasks (like functionally using the remote to

change the channel or using the screwdriver to screw in a nail) in which

dexterity enabled by redundant degrees of freedom is critical. In fact,

dexterous manipulation is defined as being object-centric, with the goal

of controlling object movement through precise control of forces and motions

— something that is not possible without the ability to simultaneously impact

the object from multiple directions. For example, using only two fingers to

attempt common tasks such as opening the lid of a jar or hitting a nail with a

hammer would quickly encounter the challenges of slippage, complex contact

forces, and underactuation. Although dexterous multi-fingered hands can indeed

enable flexibility and success of a wide range of manipulation skills, many of

these more complex behaviors are also notoriously difficult to control: They

require finely balancing contact forces, breaking and reestablishing contacts

repeatedly, and maintaining control of unactuated objects. Success in such

settings requires a sufficiently dexterous hand, as well as an intelligent

policy that can endow such a hand with the appropriate control strategy. We

study precisely this in our work on Deep Dynamics Models for Learning Dexterous

Manipulation.

Common approaches for control include modeling the system as well as the

relevant objects in the environment, planning through this model to produce

reference trajectories, and then developing a controller to actually achieve

these plans. However, the success and scale of these approaches have been

restricted thus far due to their need for accurate modeling of complex details,

which is especially difficult for such contact-rich tasks that call for precise

fine-motor skills. Learning has thus become a popular approach, offering a

promising data-driven method for directly learning from collected data rather

than requiring explicit or accurate modeling of the world. Model-free

reinforcement learning (RL) methods, in particular, have been shown to learn

policies that achieve good performance on complex tasks;

however, we will show that these state-of-the-art algorithms struggle when a

high degree of flexibility is required, such as moving a pencil to follow

arbitrary user-specified strokes, instead of a fixed one. Model-free methods

also require large amounts of data, often making them infeasible for real-world

applications. Model-based RL methods, on the other hand, can be much more

efficient, but have not yet been scaled up to similarly complex tasks. Our work

aims to push the boundary on this task complexity, enabling a dexterous

manipulator to turn a valve, reorient a cube in-hand, write arbitrary motions

with a pencil, and rotate two Baoding balls around the palm. We show that our

method of online planning with deep dynamics models (PDDM) addresses both of

the aforementioned limitations: Improvements in learned dynamics models,

together with improvements in online model-predictive control, can indeed

enable efficient and effective learning of flexible contact-rich dexterous

manipulation skills — and that too, on a 24-DoF anthropomorphic hand in the

real world, using ~4 hours of purely real-world data to coordinate multiple

free-floating objects.

Method Overview

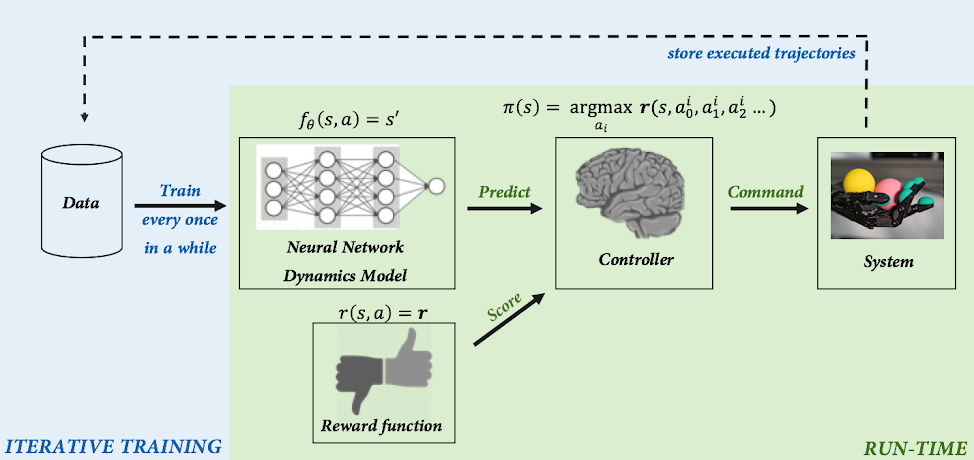

Figure 2: Overview of our PDDM algorithm for online planning with deep dynamics

models.

Learning complex dexterous manipulation skills on a real-world robotic system

requires an algorithm that is (1) data-efficient, (2) flexible, and (3)

general-purpose. First, the method must be efficient enough to learn tasks in

just a few hours of interaction, in contrast to methods that utilize

simulation and require hundreds of hours, days, or even years to learn.

Second, the method must be flexible enough to handle a variety of tasks, so

that the same model can be used to perform various different tasks. Third, the

method must be general and make relatively few assumptions: It should not

require a known model of the system, which can be very difficult to obtain for

arbitrary objects in the world.

To this end, we adopt a model-based reinforcement learning approach for

dexterous manipulation. Model-based RL methods work by learning a predictive

model of the world, which predicts the next state given the current state and

action. Such algorithms are more efficient than model-free learners because

every trial provides rich supervision: even if the robot does not succeed at

performing the task, it can use the trial to learn more about the physics of

the world. Furthermore, unlike model-free learning, model-based algorithms are

“off-policy,” meaning that they can use any (even old) data for learning.

Typically, it is believed that this efficiency of model-based RL algorithms

comes at a price: since they must go through this intermediate step of learning

the model, they might not perform as well at convergence as model-free methods,

which more directly optimize the reward. However, our simulated comparative

evaluations show that our model-based method actually performs better than

model-free alternatives when the desired tasks are very diverse (e.g., writing

different characters with a pencil). This separation of modeling from control

allows the model to be easily reused for different tasks – something that is

not as straightforward with learned policies.

Our complete method (Figure 2), consists of learning a predictive model of the

environment (denoted $f_theta(s,a) = s’$), which can then be used to control

the robot by planning a course of action at every time step through a

sampling-based planning algorithm. Learning proceeds as follows: data is

iteratively collected by attempting the task using the latest model, updating

the model using this experience, and repeating. Although the basic design of

our model-based RL algorithms has been explored in prior work, the particular

design decisions that we made were crucial to its performance. We utilize an

ensemble of models, which accurately fits the dynamics of our robotic system,

and we also utilize a more powerful sampling-based planner that preferentially

samples temporally correlated action sequences as well as performs

reward-weighted updates to the sampling distribution. Overall, we see effective

learning, a nice separation of modeling and control, and an intuitive mechanism

for iteratively learning more about the world while simultaneously reasoning at

each time step about what to do.

Baoding Balls

For a true test of dexterity, we look to the task of Baoding balls. Also

referred to as Chinese relaxation balls, these two free-floating spheres must

be rotated around each other in the palm. Requiring both dexterity and

coordination, this task is commonly used for improving finger coordination,

relaxing muscular tensions, and recovering muscle strength and motor skills

after surgery. Baoding behaviors evolve in the high dimensional workspace of

the hand and exhibit contact-rich (finger-finger, finger-ball, and ball-ball)

interactions that are hard to reliably capture, either analytically or even in

a physics simulator. Successful baoding behavior on physical hardware requires

not only learning about these interactions via real world experiences, but also

effective planning to find precise and coordinated maneuvers while avoiding

task failure (e.g., dropping the balls).

For our experiments, we use the ShadowHand — a 24-DoF five-fingered

anthropomorphic hand. In addition to ShadowHand’s inbuilt proprioceptive

sensing at each joint, we use a 280×180 RGB stereo image pair that is fed into

a separately pretrained tracker to produce 3D position estimates for the two

Baoding balls. To enable continuous experimentation in the real world, we

developed an automated reset mechanism (Figure 3) that consists of a ramp and

an additional robotic arm: The ramp funnels the dropped Baoding balls to a

specific position and then triggers the 7-DoF Franka-Emika arm to use its

parallel jaw gripper to pick them up and return them to the ShadowHand’s palm

to resume training. We note that the entire training procedure is performed

using the hardware setup described above, without the aid of any simulation

data.

Figure 3: Automated reset procedure, where the Franka-Emika arm gathers and

resets the Baoding Balls, in order for the ShadowHand to continue its training.

During the initial phase of the learning, the hand continues to drop both

balls, since that is the very likely outcome before it knows how to solve the

task. Later, it learns to keep the balls in the palm to avoid the penalty

incurred due to dropping. As learning improves, progress in terms of

half-rotations start to emerge around 30 minutes of training. Getting the balls

past this 90-degree orientation is a difficult maneuver, and PDDM spends a

moderate amount of time here: To get past this point, notice the transition

that must happen (in the 3rd video panel of Figure 4), from first controlling

the objects with the pinky, and then controlling them indirectly through hand

motion, and finally getting to control them with the thumb. By ~2 hours, the

hand can reliably make 90-degree turns, frequently make 180-degree turns, and

sometimes even make turns with multiple rotations.

Figure 4: Training progress on the ShadowHand hardware. From left to right:

0-0.25 hours, 0.25-0.5 hours, 0.5-1.5 hours, ~2 hours.

Simulated Tasks

Although we presented the PDDM algorithm in light of the Baoding task, it is

very generic, and we show it below in Figure 5 working on a suite of simulated

dexterous manipulation tasks. These tasks illustrate various challenges

presented by contact-rich dexterous manipulation tasks — high dimensionality

of the hand, intermittent contact dynamics involving hand and objects,

prevalence of constraints that must be respected and utilized to effectively

manipulate objects, and catastrophic failures from dropping objects from the

hand. These tasks not only require precise understanding of the rich contact

interactions but also require carefully coordinated and planned movements.

Figure 5: Result of PDDM solving simulated dexterous manipulation tasks. From

left to right: 9 DOF D’Claw turning valve to random (green) targets (~20 min of

data), 16 dof D’Hand pulling a weight via the manipulation of a flexible rope

(~1 hour of data), 24 DOF ShadowHand performing in-hand reorientation of a

free-floating cube to random (shown) targets (~1 hour of data), 24 DOF

ShadowHand following desired trajectories with tip of a free-floating pencil

(~1-2 hours of data). Note that the amount of data is measured in terms of the

real-world equivalent (e.g., 100 data points where each step represents 0.1

seconds would represent 10 seconds worth of data).

Model Reuse

Since PDDM learns dynamics models as opposed to task-specific policies or

policy-conditioned value functions, a given model can then be reused when

planning for different but related tasks. In Figure 6 below, we demonstrate

that the model trained for the Baoding task of performing counterclockwise

rotations (left) can be repurposed to move a single ball to a goal location in

the hand (middle) or to perform clockwise rotations (right) instead of the

learned counterclockwise ones.

Figure 6: Model reuse on simulated tasks. Left: train model on CCW Baoding

task. Middle: reuse that model for go-to single location task. Right: reuse

that same model for CW Baoding task.

Flexibility

We study the flexibility of PDDM by experimenting with handwriting, where the

base of the hand is fixed and arbitrary characters need to be written through

the coordinated movement of the fingers and wrist. Although even writing a

fixed trajectory is challenging, we see that writing arbitrary trajectories

requires a degree of flexibility and coordination that is exceptionally

challenging for prior methods. PDDM’s separation of modeling and task-specific

control allows for generalization across behaviors, as opposed to discovering

and memorizing the answer to a specific task/movement. In Figure 7 below, we

show PDDM’s handwriting results that were trained on random paths for the green

dot but then tested in a zero-shot fashion to write numerical digits.

Figure 7: Flexibility of the learned handwriting model, which was trained to

follow random paths of the green dot, but shown here to write some digits.

Future Directions

Our results show that PDDM can be used to learn challenging dexterous

manipulation tasks, including controlling free-floating objects, agile finger

gaits for repositioning objects in the hand, and precise control of a pencil to

write user-specified strokes. In addition to testing PDDM on our simulated

suite of tasks to analyze various algorithmic design decisions as well as to

perform comparisons to other state-of-the-art model-based and model-free

algorithms, we also show PDDM learning the Baoding Balls task on a real-world

24-DoF anthropomorphic hand using just a few hours of entirely real-world

interaction. Since model-based techniques do indeed show promise on complex

tasks, exciting directions for future work would be to study methods for

planning at different levels of abstraction to enable success on sparse-reward

or long-horizon tasks, as well as to study the effective integration of

additional sensing modalities, such as vision and touch, into these models to

better understand the world and expand the boundaries of what our robots can

do. Can our robotic hand braid someone’s hair? Crack an egg and carefully

handle the shell? Untie a knot? Button up all the buttons of a shirt? Tie

shoelaces? With the development of models that can understand the world, along

with planners that can effectively use those models, we hope the answer to all

of these questions will become ‘yes.’

Acknowledgements

This work was done at Google Brain, and the authors are Anusha Nagabandi,

Kurt Konoglie, Sergey Levine, and Vikash Kumar. The authors would also like to

thank Michael Ahn for his frequent software and hardware assistance, and Sherry

Moore for her work on setting up the drivers and code for working with our

ShadowHand.