Model-Based Reinforcement Learning from Pixels with Structured Latent Variable Models

Imagine a robot trying to learn how to stack blocks and push objects using

visual inputs from a camera feed. In order to minimize cost and safety

concerns, we want our robot to learn these skills with minimal interaction

time, but efficient learning from complex sensory inputs such as images is

difficult. This work introduces SOLAR, a

new model-based reinforcement learning (RL) method that can learn skills –

including manipulation tasks on a real Sawyer robot arm – directly from

visual inputs with under an hour of interaction. To our knowledge, SOLAR is the

most efficient RL method for solving real world image-based robotics tasks.

Our robot learns to stack a Lego block and push a mug onto a coaster with only

inputs from a camera pointed at the robot. Each task takes an hour or less of

interaction to learn.

In the RL setting, an agent such as our robot learns from its own experience

through trial and error, in order to minimize a cost function corresponding to

the task at hand. Many challenging tasks have been solved in recent years by RL

methods, but most of these success stories come from model-free RL methods,

which typically require substantially more data than model-based

methods. However, model-based methods often

rely on the ability to accurately predict into the future in order to plan the

agent’s actions. This is an issue for image-based learning as predicting future

images itself requires large amounts of

interaction, which we wish to avoid.

There are some model-based RL methods that do not require accurate future

prediction, but these methods typically place stringent assumptions on the

state. The LQR-FLM method has been shown to

learn new tasks very efficiently, including for real robotic systems, by

modeling the dynamics of the state as approximately linear. This assumption,

however, is prohibitive for image-based learning, as the dynamics of pixels in

a camera feed are far from linear. The question we study in our work is: how

can we relax this assumption in order to develop a model-based RL method that

can solve image-based tasks without requiring accurate future predictions?

We tackle this problem by learning a latent state representation using deep

neural networks. When our agent is faced with images from the task, it can

encode the images into their latent representations, which can then be used

as the state inputs to LQR-FLM rather than the images themselves. The key

insight in SOLAR is that, in addition to learning a compact latent state that

accurately captures the objects, we specifically learn a representation that

works well with LQR-FLM by encouraging the latent dynamics to be linear. To

that end, we introduce a latent variable model that explicitly represents

latent linear dynamics, and this model combined with LQR-FLM provides the basis

for the SOLAR algorithm.

Stochastic Optimal Control with Latent Representations

SOLAR stands for stochastic optimal control with latent

representations, and it is an efficient and general solution for

image-based RL settings. The key ideas behind SOLAR are learning latent state

representations where linear dynamics are accurate, as well as utilizing a

model-based RL method that does not rely on future prediction, which we

describe next.

Linear Dynamical Control

Using the system state, LQR-FLM and related methods have been used to

successfully learn a myriad of tasks including robotic manipulation and

locomotion. We aim to extend these capabilities by automatically learning the

state input to LQR-FLM from images.

One of the best-known results in control theory is the linear-quadratic

regulator

(LQR), a set of equations that provides the optimal control strategy for a

system in which the dynamics are linear and the cost is quadratic. Though real

world systems are almost never linear, approximations to LQR such as LQR with

fitted linear

models (LQR-FLM)

have been shown to perform well at a variety of robotic control tasks. LQR-FLM

has been one of the most efficient RL methods at learning control skills, even

compared to other model-based RL methods. This efficiency is enabled by the

simplicity of linear models as well as the fact that these models do not need

to predict accurately into the future. This makes LQR-FLM an appealing method

to build from, however the key limitation of this method is that it normally

assumes access to the system state, e.g., the joint configuration of the

robot and the positions of objects of interest, which can often be reasonably

modeled as approximately linear. We instead work from images and relax this

assumption by learning a representation that we can use as the input to

LQR-FLM.

Learning Latent States from Images

The graphical model we set up presumes that the images we observe are a

function of a latent state, and the states evolve according to linear dynamics

modulated by actions, and where the costs are given by a quadratic function of

the state and action.

We want our agent to extract, from its visual input, a state representation

where the dynamics of the state are as close to linear as possible. To

accomplish this, we devise a latent variable model in which the latent states

obey linear dynamics, as detailed in the graphic above. The dark nodes are what

we observe from interacting with the environment – namely, images, actions

taken by the agent, and costs. The light nodes are the underlying states, which

is the representation that we wish to learn, and we posit that the next state

is a linear function of the current state and action. This model bears strong

resemblance to the structured variational

auto-encoder (SVAE), a model previously

applied to applications such as characterizing videos of mice. The method that

we use to fit our model is also based off of the method presented in this prior

work.

At a high level, our method learns both the state dynamics and an encoder,

which is a function that takes as input the current and past images and outputs

a guess of the current state. If we encode many observation sequences

corresponding to the agent’s interactions with the environment, we can see if

these state sequences behave according to our learned linear dynamics – if

they don’t, we adjust our dynamics and our encoder to bring them closer in

line. One key aspect of this procedure is that we do not directly optimize our

model to be accurate at predicting into the future, since we only fit linear

models retrospectively to the agent’s previous interactions. This strongly

complements LQR-FLM which, again, does not rely on prediction for good

performance. Our paper provides more

details about our model learning procedure.

The SOLAR Algorithm

Our robot iteratively interacts with its environment, uses this data to update

its model, uses this model to estimate the latent states and their dynamics,

and uses these dynamics to update its behavior.

Now that we have described the building blocks of our method, how do these

pieces fit together into the SOLAR method? The agent acts in the environment

according to its policy, which prescribes actions based on the current latent

state estimate. These interactions produce trajectories of images, actions, and

costs that are then used to fit the model detailed in the previous section.

Afterwards, using these entire trajectories of interactions, our model

retrospectively refines its estimate of the latent dynamics, which allows

LQR-FLM to produce an updated policy that should perform better at the given

task, i.e., incur lower costs. The updated policy is then used to collect more

trajectories, and the procedure repeats. The graphic above depicts these stages

of the algorithm.

The key difference between LQR-FLM and most other model-based RL methods is

that the resulting models are only used for policy improvement and not for

prediction into the future. This is useful in settings where the observations

are complex and difficult to predict, and we extend this benefit into

image-based settings by introducing latent states that we can estimate

alongside the dynamics. As seen in the next section, SOLAR can produce good

policies for image-based robotic manipulation tasks using only one hour of

interaction time with the environment.

Experiments

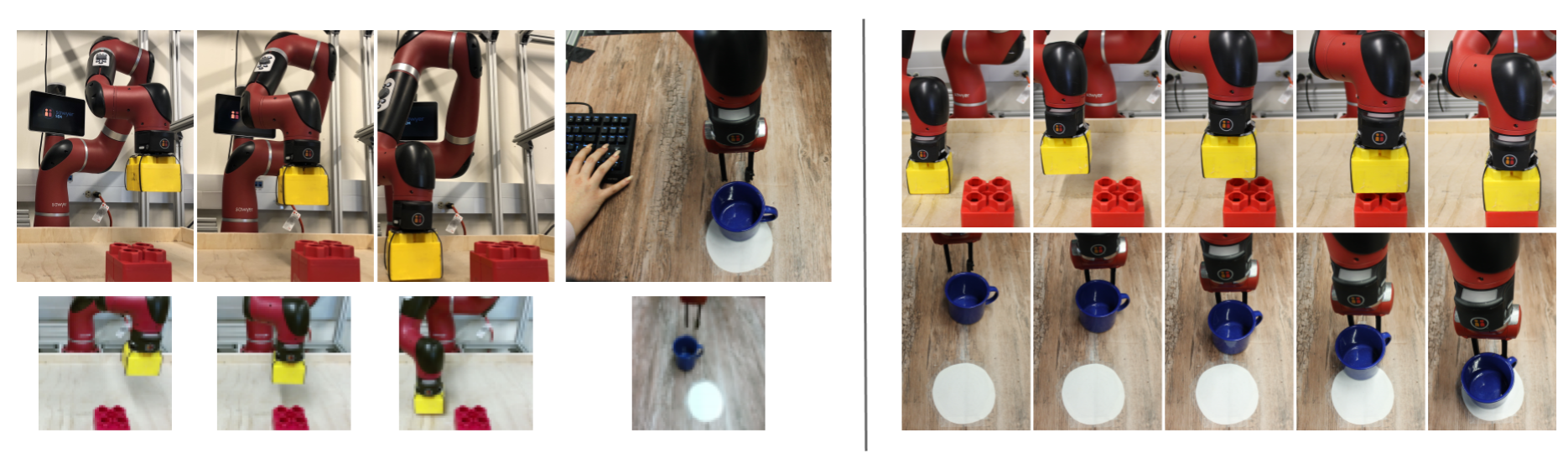

Left: For Lego block stacking, we experiment with multiple starting positions

of the arm and block. For pushing, we only use sparse rewards provided by a

human pushing a key when the robot succeeds. Example image observations are

given in the bottom row. Right: Examples of successful behaviors learned by

SOLAR.

Our main testbed for SOLAR is the Sawyer robotic arm, which has seven degrees

of freedom and can be used for a variety of manipulation tasks. We feed the

robot images from a camera pointed at its arm and the relevant objects in the

scene, and we task our robot with learning Lego block stacking and mug pushing,

as detailed below.

Lego Block Stacking

<!–

–>

Using SOLAR, our Sawyer robot efficiently learns stacking from only image

observations from all three initial positions. The ablations are less

successful, and DVF does not learn as quickly as SOLAR. In particular, these

methods have difficulty with the challenging setting where the block starts on

the table.

The main challenge for block stacking stems from the precision required to

succeed, as the robot must very accurately place the block in order to properly

connect the pieces. Using SOLAR, the Sawyer learns this precision from only the

camera feed, and moreover the robot can successfully learn to stack from a

number of starting configurations of the arm and block. In particular, the

configuration where the block starts on the table is the most challenging, as

the Sawyer must learn to first lift the block off the table before stacking it

– in other words, it can’t be “greedy” and simply move toward the other block.

We first compare SOLAR to an ablation that uses a standard

variational

auto-encoder (VAE) rather than the SVAE,

which means that the state representation is not learned to follow linear

dynamics. This ablation is only successful on the easiest starting

configuration. In order to understand what benefits we extract from not

requiring accurate future predictions, we compare to another ablation which

replaces LQR-FLM with an alternative planning method known as model-predictive

control (MPC), and we also compare to a state-of-the-art prior method that uses

MPC, deep visual foresight (DVF). MPC has

been used in a number of prior and

subsequent works, and it relies on being

able to generate accurate future predictions using the learned model in order

to determine what actions are likely to lead to good performance.

The MPC ablation learns more quickly on the two easier configurations, however,

it fails in the most difficult setting because MPC greedily reduces the

distance between the two blocks rather than lifting the block off the table.

MPC acts greedily because it only plans over a short horizon, as predicting

future images becomes increasingly inaccurate over longer horizons, and this is

exactly the failure mode that SOLAR is able to overcome by utilizing LQR-FLM to

avoid future predictions altogether. Finally, we find that DVF can make

progress but ultimately is not able to solve the two harder settings even with

more data than what we use for our method. This highlights our method’s data

efficiency, as we use in total a few hours of robot data compared to days or

weeks of data as in DVF.

Mug Pushing

Despite the challenge of only having sparse rewards provided by a

human key press, our robot running SOLAR learns to push the mug onto the

coaster in under an hour. DVF is again not as efficient and does not learn as

quickly as SOLAR.

We add an additional challenge to mug pushing by replacing the costs with a

sparse reward signal, i.e., the robot only gets told when it has completed

the task, and it is told nothing otherwise. As seen in the picture above, the

human presses a key on the keyboard in order to provide the sparse reward, and

the robot must reason about how improve its behavior in order to achieve this

reward. This is implemented via a straightforward extension to SOLAR, as we

detail in the paper. Despite this

additional challenge, our method learns a successful policy in about an hour of

interaction time, whereas DVF performs worse than our method using a comparable

amount of data.

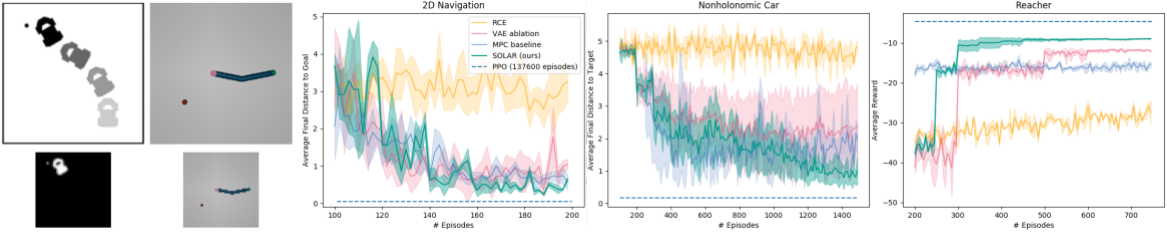

Simulated Comparisons

Left: an illustration of the car and reacher environments we experiment with,

along with example image observations in the bottom row. Right: our method

generally performs better than the ablations we compare to, as well as RCE. PPO

has better final performance, however PPO requires one to three orders of

magnitude more data than SOLAR to reach this performance.

In addition to the Sawyer experiments, we also run several comparisons in

simulation, as most prior work does not experiment with real robots. In

particular, we set up a 2D navigation domain where the underlying system

actually has linear dynamics and quadratic cost, but we can only observe images

that show a top-down view of the agent and the goal. We also include two

domains that are more complex: a car that must drive from the bottom right to

the top left of a 2D plane, and a 2 degree of freedom arm that is tasked with

reaching to a goal in the bottom left. All domains are learned with only image

observations that provide a top down view of the task.

We compare to robust locally-linear controllable

embeddings (RCE), which takes a different

approach to learning latent state representations that follow linear dynamics.

We also compare to proximal policy

optimization (PPO), a model-free RL method

that has been used to solve a number of simulated robotics domains but is not

data efficient enough for real world learning. We find that SOLAR learns faster

and achieves better final performance than RCE. PPO typically learns better

final performance than SOLAR, but this typically requires one to three orders

of magnitude more data, which again is prohibitive for most real world learning

tasks. This kind of tradeoff is typical: model-free methods tend to achieve

better final performance, but model-based methods learn much faster. Videos of

the experiments can be viewed on our project

website.

Related Work

Approaches to learning latent representations of images have proposed

objectives such as reconstructing the image

and predicting future images. These

objectives do not line up perfectly with our objective of accomplishing tasks

– for example, a robot tasked with sorting objects into bins by color does not

need to perfectly reconstruct the color of the wall in front of it. There has

also been work on learning state representations that are suitable for control,

including identifying points of interest

within the image and learning latent states such that dimensions are

independently controllable. A recent survey

paper categorizes the landscape of state

representation learning.

Separately from control, there has been a number of recent works that learn

structured representations of data, many of which extend VAEs. The SVAE is an

example of one such framework, and some

other

methods also attempt to explain the data

with linear dynamics. Beyond this, there have been works that learn latent

representations with mixture model

structure,

various

discrete

structures, and Bayesian

nonparametric

structures.

Ideas that are closely related to ours have been proposed in prior and

subsequent work. As mentioned before, DVF has also learned robotics tasks

directly from vision, and a recent blog

post summarizes their

results. Embed to control and its successor

RCE also aim to learn latent state representations with linear dynamics. We

compare to these methods in our paper and demonstrate that our method tends to

exhibit better performance. Subsequent to our work,

PlaNet learns latent state representations

with a mixture of deterministic and stochastic variables and uses them in

conjunction with MPC, one of the baseline methods in our evaluation,

demonstrating good results on several simulated tasks. As shown by our

experiments, LQR-FLM and MPC each have their respective strengths and

weaknesses, and we found that LQR-FLM was typically more successful for robotic

control, avoiding the greedy behavior of MPC.

Future Work

We see several exciting directions for future work, and we’ll briefly mention

two. First, we want our robots to be able to learn complex, multi-stage tasks,

such as building Lego structures rather than just stacking one block, or

setting a table rather than just pushing one mug. One way we may realize this

is by providing intermediate images of the goals we want the robot to

accomplish, and if we expect that the robot can learn each stage separately, it

may be able to string these policies together into more complex and interesting

behaviors. Second, humans don’t just learn representations of states but also

actions – we don’t think about individual muscle movements, we group such

movements together into “macro-actions” to perform highly coordinated and

sophisticated behaviors. If we can similarly learn action representations, we

can enable our robots to more efficiently learn how to use hardware such as

dexterous hands, which will further increase their ability to handle complex,

real-world environments.

This post is based on the following paper:

- Marvin Zhang*, Sharad Vikram*, Laura Smith, Pieter Abbeel, Matthew J. Johnson, Sergey Levine.

SOLAR: Deep Structured Representations for Model-Based Reinforcement Learning.

International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), 2019.

Project webpage

Open-source code

We would like to thank our co-authors, without whom this work would not be

possible, for also contributing to and providing feedback on this post, in

particular Sergey Levine. We would also like to thank the many people that have

provided insightful discussions, helpful suggestions, and constructive reviews

that have shaped this work.