Robots that Learn to Adapt

Figure 1: Our model-based meta reinforcement learning algorithm enables a

legged robot to adapt online in the face of an unexpected system

malfunction (note the broken front right leg).

Humans have the ability to seamlessly adapt to changes in their environments:

adults can learn to walk on crutches in just a few seconds, people can adapt

almost instantaneously to picking up an object that is unexpectedly heavy, and

children who can walk on flat ground can quickly adapt their gait to walk

uphill without having to relearn how to walk. This adaptation is critical for

functioning in the real world.

Robots, on the other hand, are typically deployed with a fixed behavior (be it

hard-coded or learned), allowing them succeed in specific settings, but leading

to failure in others: experiencing a system malfunction, encountering a new

terrain or environment changes such as wind, or needing to cope with a payload

or other unexpected perturbations. The idea behind our latest research is that

the mismatch between predicted and observed recent states should inform the

robot to update its model into one that more accurately describes the current

situation. Noticing our car skidding on the road, for example, informs us that

our actions are having a different effect than expected, and thus allows us to

plan our consequent actions accordingly (Fig. 2). In order for our robots to be

successful in the real world, it is critical that they have this ability to use

their past experience to quickly and flexibly adapt. To this effect, we

developed a model-based meta-reinforcement learning algorithm capable of fast

adaptation.

Figure 2: The driver normally makes decisions based on his/her model of the

world. Suddenly encountering a slippery road, however, leads to unexpected

skidding. Online adaptation of the driver’s world model based on just a few of

these observations of model mismatch allows for fast recovery.

Fast Adaptation

Prior work has used (a) trial-and-error adaptation approaches (Cully et al.,

2015) as well as (b) model-free meta-RL approaches (Wang et al., 2016;

Finn et al., 2017) to enable agents to adapt after a handful of trials.

However, our work takes this adaptation ability to the extreme. Rather than

adaptation requiring a few episodes of experience under the new settings, our

adaptation happens online on the scale of just a few timesteps (i.e.,

milliseconds): so fast that it can hardly be noticed.

We achieve this fast adaptation through the use of meta-learning (discussed

below) in a model-based learning setup. In the model-based setting, rather than

adapting based on the rewards that are achieved during rollouts, data for

updating the model is readily available at every timestep in the form of model

prediction errors on recent experiences. This model-based approach enables the

robot to meaningfully update the model using only a small amount of recent

data.

Method Overview

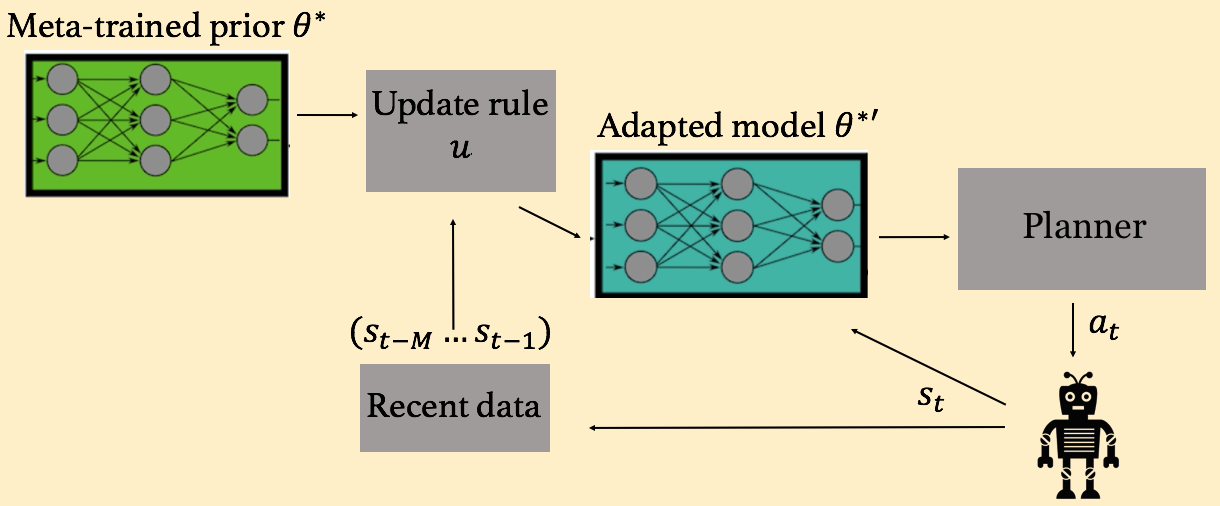

Fig 3. The agent uses recent experience to fine-tune the prior model into an

adapted one, which the planner then uses to perform its action selection. Note

that we omit details of the update rule in this post, but we experiment with

two such options in our work.

Our method follows the general formulation shown in Fig. 3 of using

observations from recent data to perform adaptation of a model, and it is

analogous to the overall framework of adaptive control (Sastry and Isidori,

1989; Åström and Wittenmark, 2013). The real challenge here, however, is how to

successfully enable model adaptation when the models are complex, nonlinear,

high-capacity function approximators (i.e., neural networks). Naively

implementing SGD on the model weights is not effective, as neural networks

require much larger amounts of data in order to perform meaningful learning.

Thus, we enable fast adaptation at test time by explicitly training with this

adaptation objective during (meta-)training time, as explained in the following

section. Once we meta-train across data from various settings in order to get

this prior model (with weights denoted as theta^*) that is good at

adaptation, the robot can then adapt from this theta^* at each time step

(Fig. 3) by using this prior in conjunction with recent experience to fine-tune

its model to the current setting at hand, thus allowing for fast online

adaptation.

Meta-training:

At any given time step t, we are in state s_t, we take action a_t,

and we end up in some resulting state s_{t+1} according to the underlying

dynamics function s_{t+1} = f(s_t, a_t). The true dynamics are unknown to

us, so we instead want to fit some learned dynamics model hat{s}_{t+1} =

f_{theta}(s_t, a_t) that makes predictions as well as possible on observed

data points of the form (s_t, a_t, s_{t+1}). Our planner can use this

estimated dynamics model in order to perform action selection.

Assuming that any detail or setting could have changed at any time step along

the rollout, we consider temporally-close time steps as being able to inform us

about the “task” details of our current situation: operating in different parts

of the state space, enduring disturbances, attempting new goals/reward,

experiencing a system malfunction, etc. Thus, in order for our model to be the

most useful for planning, we want to first update it using our recently

observed data.

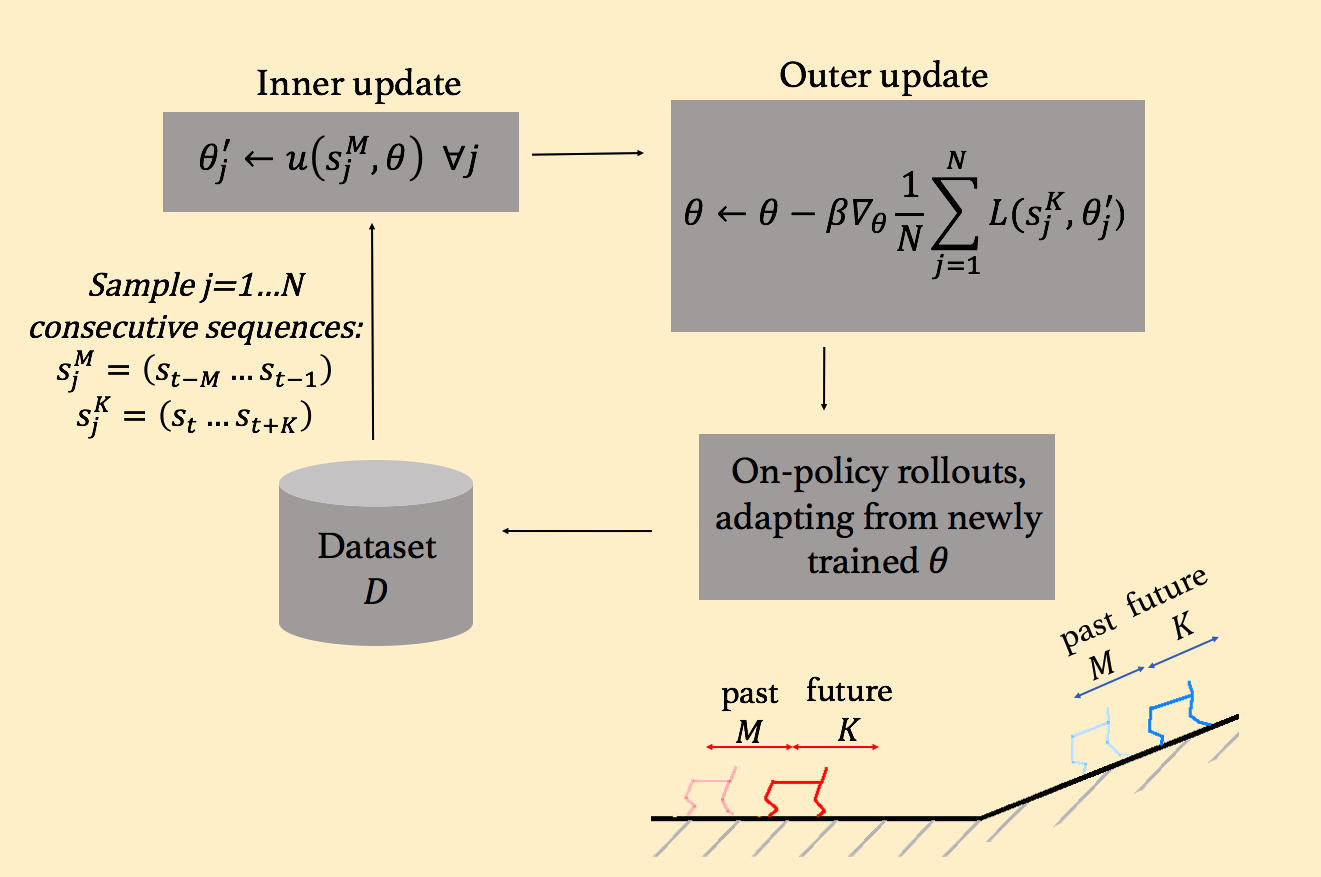

At training time (Fig. 4), what this amounts to is selecting a consecutive

sequence of (M+K) data points, using the first M to update our model weights

from theta to theta’, and then optimizing for this new theta’ to

be good at predicting the state transitions for the next K time steps. This

newly formulated loss function represents prediction error on the future K

points, after adapting the weights using information from the past K points:

L = sum_{text{tasks}} | f_{theta’}(s, a) – s’ | ^ 2 |_{text{data}_K}

where

theta’ = u(theta, text{data}_M)

In other words, theta does not need to result in good dynamics

predictions. Instead, theta needs to be such that it can use task-specific

(i.e. recent) data points to quickly adapt itself into new weights that do

result in good dynamics predictions. See the MAML blog post for more

intuition on this formulation.

Fig 4. Meta-training procedure for obtaining a $theta$ such that the

adaptation of $theta$ using the past $M$ timesteps of experience produces a

model that performs well for the future $K$ timesteps.

Simulation Experiments

We conducted experiments on simulated robotic systems to test the ability of

our method to adapt to sudden changes in the environment, as well as to

generalize beyond the training environments. Note that we meta-trained all

agents on some distribution of tasks/environments (see paper for details), but

we then evaluated their adaptation ability on unseen and changing environments

at test time. Figure 5 shows a cheetah robot that was trained on piers of

varying random buoyancy, and then tested on a pier with sections of varying

buoyancy in the water. This environment demonstrates the need for not only

adaptation, but for fast/online adaptation. Figure 6 also demonstrates the need

for online adaptation by showing an ant robot that was trained with different

crippled legs, but tested on an unseen leg failure occurring part-way through a

rollout. In these qualitative results below, we compare our gradient-based

adaptive learner (‘GrBAL’) to a standard model-based learner (‘MB’) that was

trained on the same variation of training tasks but has no explicit mechanism

for adaptation.

Fig 5. Cheetah: Both methods are trained on piers of varying buoyancy. Ours is

able to perform fast online adaptation at run-time to cope with changing

buoyancy over the course of a new pier.

Fig 6. Ant: Both methods are trained on different joints being crippled. Ours

is able to use its recent experiences to adapt its knowledge and cope with an

unexpected and new malfunction in the form of a crippled leg (for a leg that

was never seen as crippled during training).

The fast adaptation capabilities of this model-based meta-RL method allow our

simulated robotic systems to attain substantial improvement in performance

and/or sample efficiency over prior state-of-the-art methods, as well as over

ablations of this method with the choice of yes/no online adaptation, yes/no

meta-training, and yes/no dynamics model. Please refer to our paper for these

quantitative comparisons.

Hardware Experiments

Fig 7. Our real dynamic legged millirobot, on which we successfully employ our

model-based meta-reinforcement learning algorithm to enable online

adaptation to disturbances and new settings such as traversing a slippery

slope, accommodating payloads, accounting for pose miscalibration errors, and

adjusting to a missing leg.

To highlight not only the sample efficiency of our meta reinforcement learning

approach, but also the importance of fast online adaptation in the real world,

we demonstrate our approach on a real dynamic legged millirobot (see Fig 7).

This small 6-legged robot presents a modeling and control challenge in the form

of highly stochastic and dynamic movement. This robot is an excellent candidate

for online adaptation for many reasons: the rapid manufacturing techniques and

numerous custom-design steps used to construct this robot make it impossible to

reproduce the same dynamics each time, its linkages and other body parts

deteriorate over time, and it moves very quickly and dynamically as a function

of its terrain.

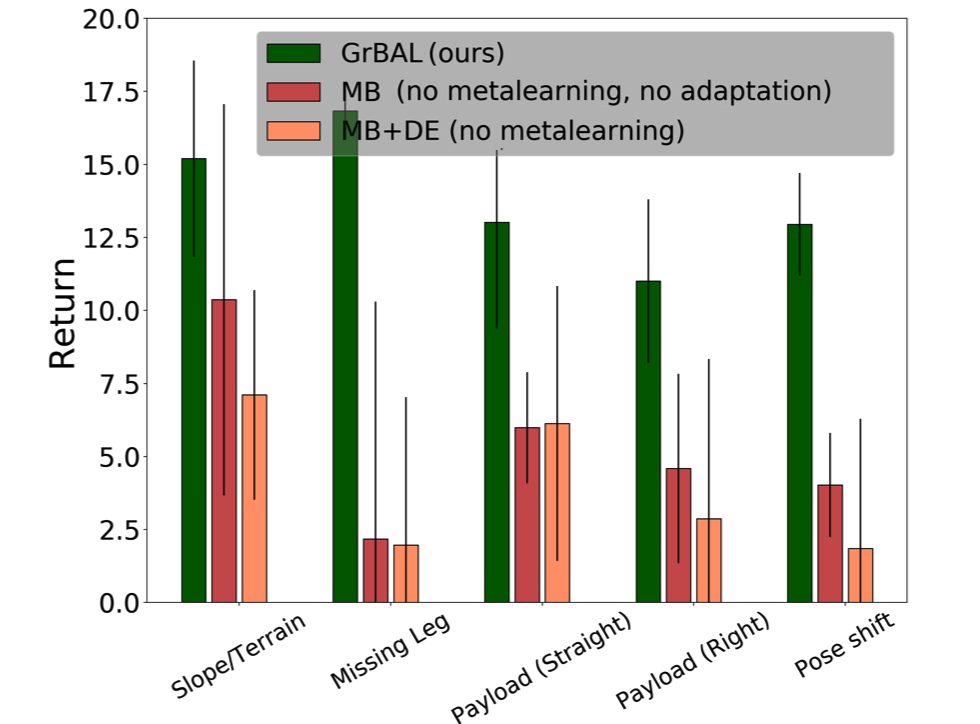

We meta-train this legged robot on various terrains, and we then test the

agent’s learned ability to adapt online to new tasks (at run-time) including a

missing leg, novel slippery terrains and slopes, miscalibration or errors in

pose estimation, and new payloads to be pulled. Our hardware experiments

compare our method to (a) standard model-based learning (‘MB’), with neither

adaptation nor meta-learning, and well as (b) a dynamic evaluation (‘MB+DE’)

comparison having adaptation, but performing the adaptation from a

non-meta-learned prior. These results (Fig. 8-10) show the need for not only

adaptation, but adaptation from an explicitly meta-learned prior.

Fig 8. Missing leg.

Fig 9. Payload.

Fig 10. Miscalibrated Pose.

By effectively adapting online, our method prevents drift from a missing leg,

prevents sliding sideways down a slope, accounts for pose miscalibration

errors, and adjusts to pulling payloads. Note that these tasks/environments

share enough commonalities with the locomotion behaviors learned during the

meta-training phase such that it would be useful to draw from that prior

knowledge (rather than learn from scratch), but they are different enough that

they do require effective online adaptation for success.

Fig 11. The ability to draw from prior knowledge as well as to learn from

recent knowledge enables GrBAL (ours) to clearly outperform both MB and MB+DE

when tested on environments that (1) require online adaptation and/or (2) were

never seen during training.

Future Directions

This work enables online adaptation of high-capacity neural network dynamics

models, through the use of meta-learning. By allowing local fine-tuning of a

model starting from a meta-learned prior, we preclude the need for an accurate

global model, as well as allow for fast adaptation to new situations such as

unexpected environmental changes. Although we showed results of adaptation on

various tasks in both simulation and hardware, there remain numerous relevant

avenues for improvement.

First, although this setup of always fine-tuning from our pre-trained prior can

be powerful, one limitation of this approach is that even numerous times of

seeing a new setting would result in the same performance as the 1st time of

seeing it. In this follow-up work, we take steps to address precisely this

issue of improving over time, while simultaneously not forgetting older skills

as a consequence of experiencing new ones.

Another area for improvement includes formulating conditions or an analysis of

the capabilities and limitations of this adaptation: what can or cannot be

adapted to, given the knowledge contained in the prior? For example, consider

two humans learning to ride a bicycle who suddenly experience a slippery road.

Assume that neither of them have ridden a bike before, so they have never

fallen off a bike before. Human A might fall, break their wrist, and require

months of physical therapy. Human B, on the other hand, might draw from his/her

prior knowledge of martial arts and thus implement a good “falling” procedure

(i.e., roll onto your back instead of trying to break a fall with the wrist).

This is a case when both humans are trying to execute a new task, but other

experiences from their prior knowledge significantly affect the result of their

adaptation attempt. Thus, having some mechanism for understanding limitations

of adaptation, under the existing prior, would be interesting.

We would like to thank Sergey Levine and Chelsea Finn for their feedback during

the preparation of this blog post. We would also like to thank our co-authors

Simin Liu, Ronald Fearing, and Pieter Abbeel. This post is based on the

following paper:

- Learning to Adapt in Dynamic, Real-World Environments Through Meta-Reinforcement Learning

A Nagabandi*, I Clavera*, S Liu, R Fearing, P Abbeel, S Levine, C Finn

International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR) 2019

Arxiv, Code, Project Page

For more information, check out the links above, and come see us at our poster

presentation at ICLR 2019 in New Orleans!