Can We Learn the Language of Proteins?

The incredible success of BERT in Natural Language Processing (NLP) showed that large models trained on unlabeled data are able to learn powerful representations of language. These representations have been shown to encode information about syntax and semantics. In this blog post we ask the question: Can similar methods be applied to biological sequences, specifically proteins? If so, to what degree do they improve performance on protein prediction problems that are relevant to biologists?

We discuss our recent work on TAPE: Tasks Assessing Protein Embeddings (preprint) (github), a benchmarking suite for protein representations learned by various neural architectures and self-supervised losses. We also discuss the challenges that proteins present to the ML community, previously described by xkcd:

Proteins Do Everything

Well, pretty much everything. As you read this, hemoglobin in your blood is moving oxygen to your muscles, transporter proteins are pumping sodium to create the action potentials necessary for your neurons to fire, and photoreceptor proteins in your eye are distinguishing between the boundaries of the letters in this sentence. Understanding what causes the disruption of a protein’s natural function can help us understand the molecular basis of disease, and lead to better treatments.

While networks of naturally-evolved proteins perform the necessary functions to keep you alive, artificially developed proteins are being spliced into bacterial genomes and put to work diligently producing insulin, breaking down plastic waste, and creating laundry detergent. Understanding how to modify proteins to adapt to user-defined functions can help make production more efficient, and enable the development of proteins with brand new functions.

Proteins 101: In Case You Ditched a Lot in High School

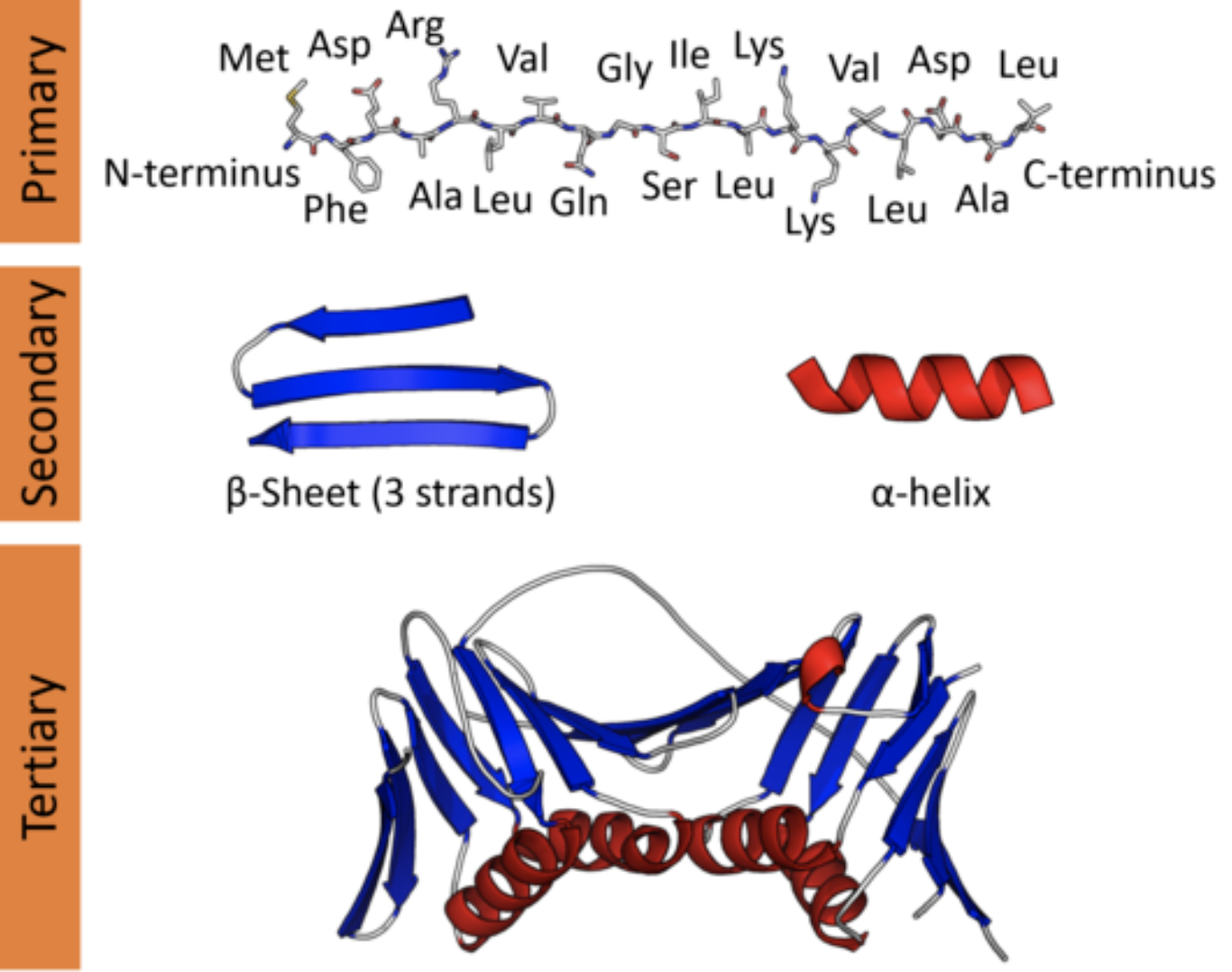

A protein is a linear chain of amino acids connected by covalent bonds. There are 20 standard amino acids. This “alphabet” lets us represent a protein as a sequence of discrete tokens, just as we might encode a sentence of English. This discrete sequential representation is known as a protein’s primary structure.

<!–

Figure 1: Our alphabet: the 20 standard amino acids (+ “U”/Selenocysteine), grouped according to their biophysical properties.

–>

A protein fragment represented as a sequence of letters in the amino acid alphabet.

In a cell, however, a protein is a three-dimensional molecular object. Since a protein’s function is performed through physical and chemical interaction with its structure, understanding this 3D structure is key to piecing together its biological role. The local geometry of a protein is known as secondary structure, and plays a role in the behavior of different segments of the protein. The global geometry of a protein is known as tertiary structure, and determines the behavior of the protein as a whole.

Protein structure at varying scales: primary structure (sequence), secondary structure (local topology), and tertiary structure (global topology).

… but what does this protein do?

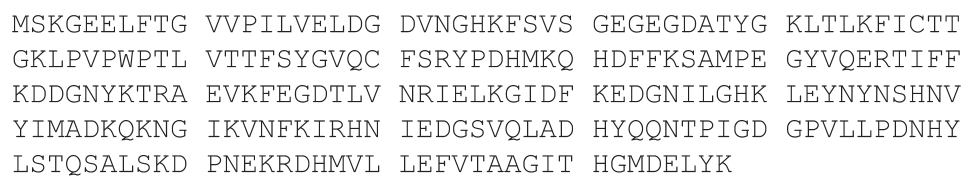

Let’s say we hand you this sequence.

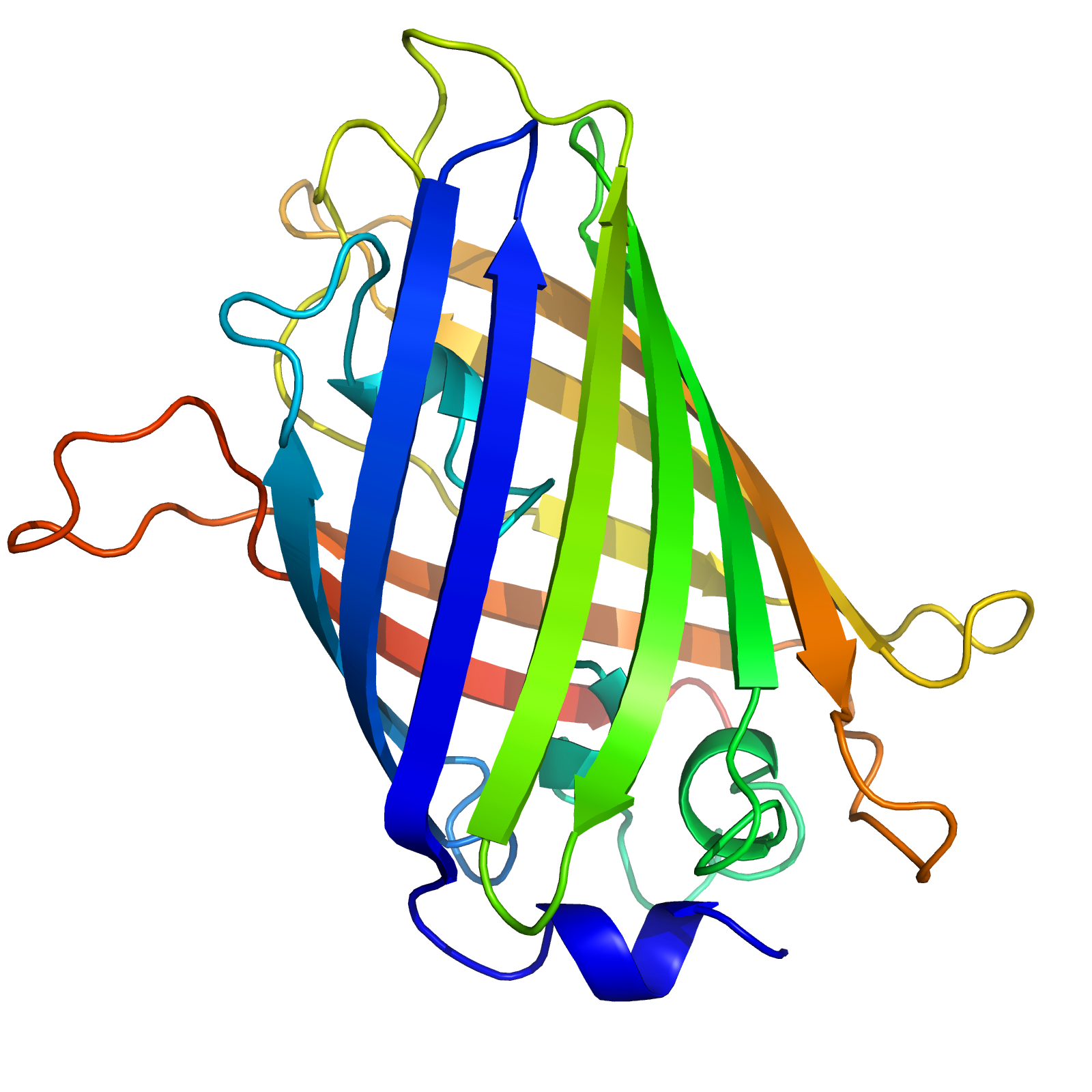

Your goal is to specify the 3D coordinates for each position in the sequence, corresponding to a biophysically reasonable conformation. In this case, the structure looks like this.

The 3D structure of the green fluorescent protein (GFP), isolated from the jellyfish Aequorea victoria. The gradient in color represents the index within the sequence from start to end.

This is a fundamental challenge of biochemistry, arguably one of the hardest prediction

tasks out there. So hard, in fact, that DeepMind wants to get in on the action. Which is, let’s face it, probably why anyone is reading this.

To do supervised learning for this problem, you need labels. In this case, a labeled protein is the three-dimensional coordinates for every atom in the molecule. Labeling a single protein is the result of a labor-intensive, resource-intensive and time-consuming process that can only be performed by experts (yes, to the O(1) structural biologists reading, we’re talking about you and your $10K/hour microscopes). Every year, we solve the structures of more and more proteins, but the number of sequences is growing exponentially compared to the number of structures.

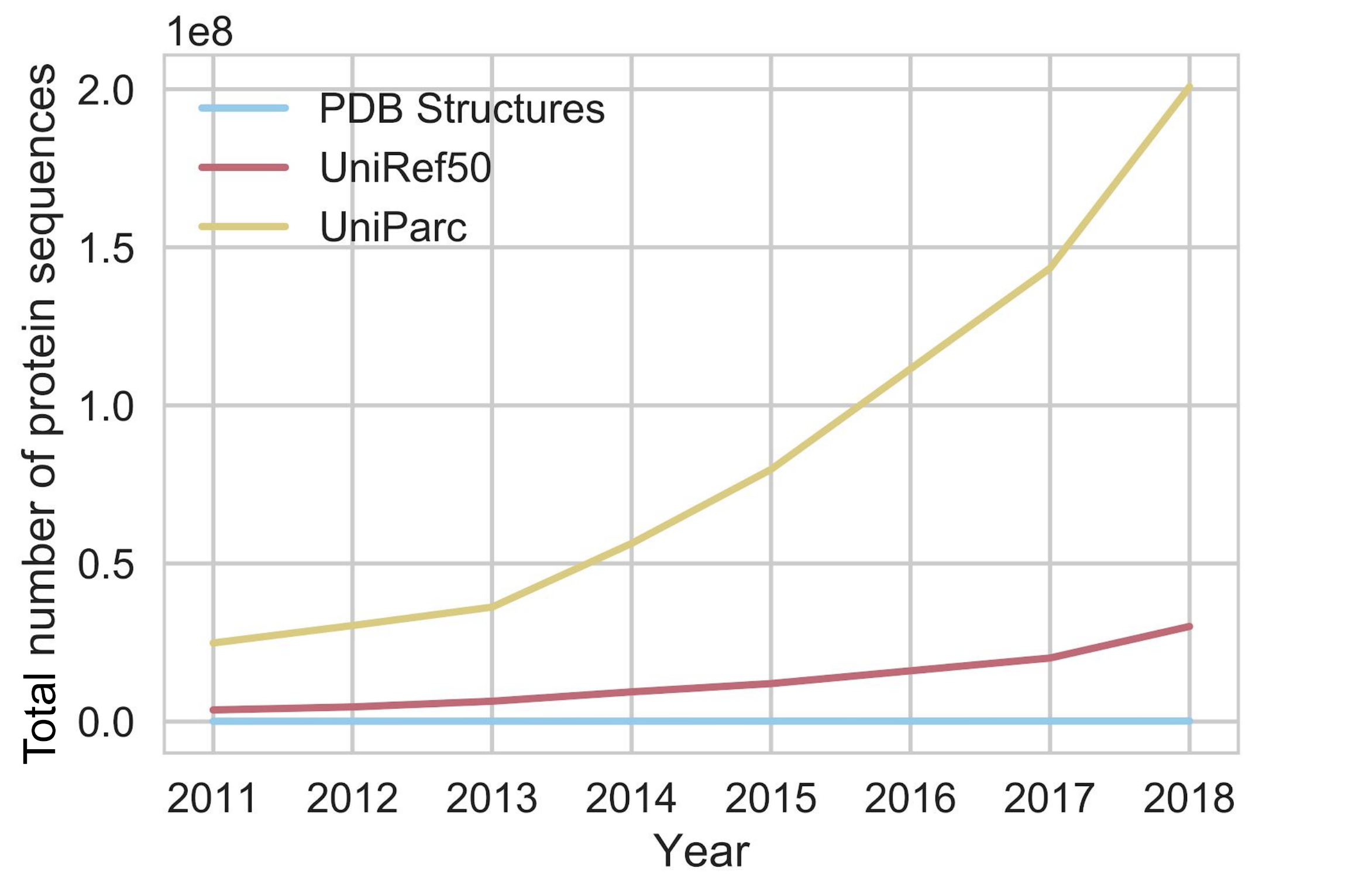

The exponential growth of sequence databases. Currently, there are about 300,000,000 sequences in UniParc, and about 160,000 structures in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) (source)

Clearly we would like to bring in some outside information.

How I Learned To Stop Worrying and Love Unlabeled Data

The good news is that there are *lots* of unlabeled protein sequences available —

from tens to hundreds of millions, depending on the database you use. If we can extract useful information from these large databases, they could provide us with a powerful source of signal.

Currently the dominant paradigm for using these databases is sequence alignment. We take our query sequence and scan it against the entire database, looking for other “cousin” sequences that are evolutionarily related (i.e. are descendants of a common genetic ancestor). In the simplest case, if we find a cousin sequence with a solved structure, we can map the cousin’s structure onto the aligned positions of our query sequence.

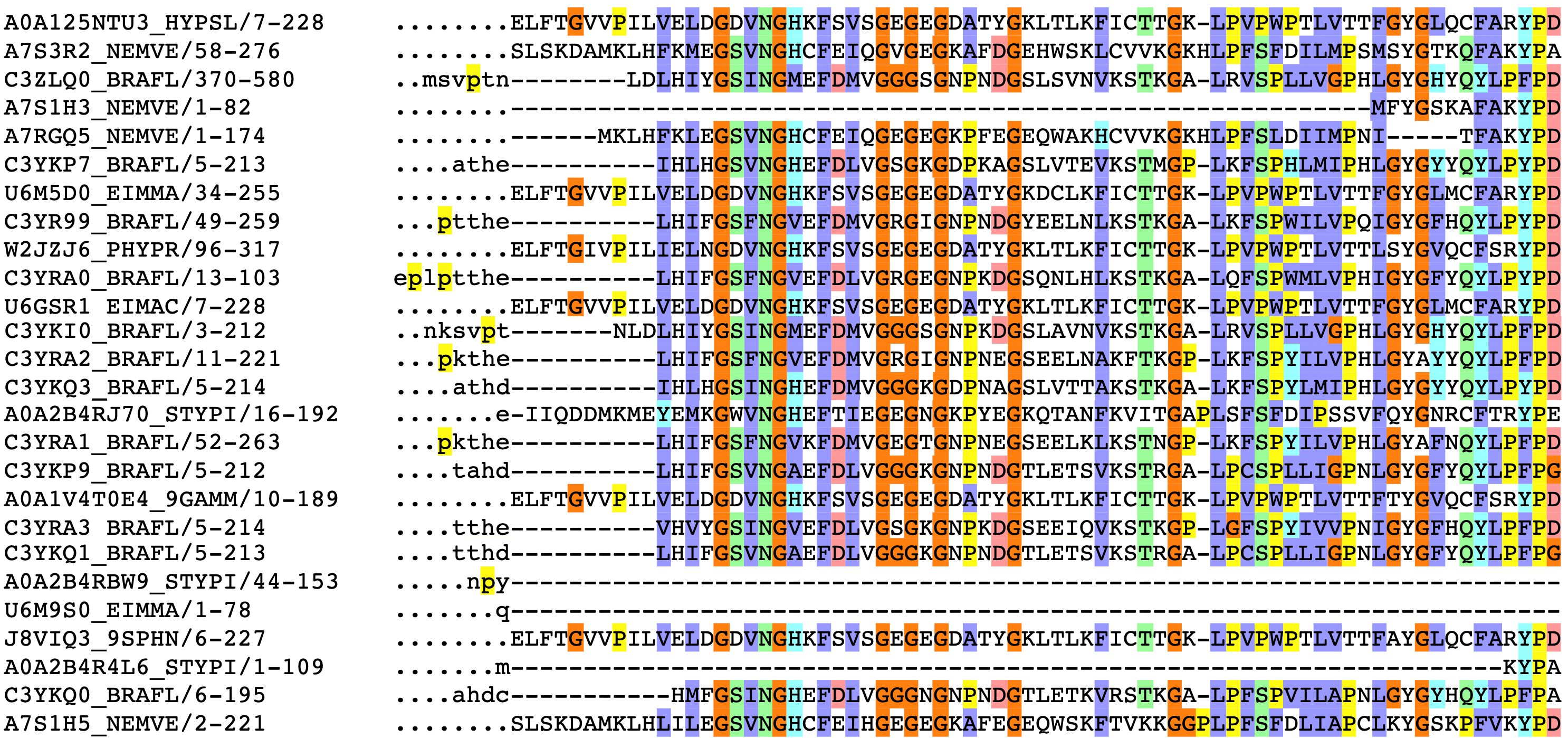

Partial sequence alignment for the GFP protein family. The jellyfish Aequorea victoria isn’t the only organism to produce a green fluorescent protein. The rows above correspond to other species’ solutions to fluorescence, such as sea anenomes, lancelets, and potato fungus.

The column on the left has the ID of the sequence, followed by the positions of that sequence represented in the alignment. Colors correspond to amino acid groupings based on biophysical properties:

purple for hydrophobic

(C, A, V, L, I, M, F, W),

red for charged

(D, E, R, K),

green for polar + uncharged

(S, T, N, Q) etc. Columns with a consistent color represent evolutionarily conserved positions.

Dots (.) and dashes (-) correspond to gaps, i.e. where an insertion or deletion has been observed.

What do evolutionary relationships buy us? Evolution is constrained; if a modification to a protein causes its structure to be disrupted, the organism will lose that function and be impaired. Thus we hope that the extracted set of cousins from the database show us where evolution had free reign, where it had some room to wiggle, and where its hands are completely tied. These representations of protein families, aptly called Multiple Sequence Alignments, are crucial inputs to protein structure prediction pipelines. Intuitively, positions that are close in 3D space will co-evolve, i.e. a mutation at one position will commonly co-occur with an accommodating mutation at the other.

There are many variations on this theme, but all boil down to using an evolutionary model to either query for related sequences or extract features from the model directly. As always, evolution provides a powerful paradigm for thinking about biological problems!

Learning the Language of Proteins via Self-Supervision

Large corpuses… difficulty of getting labels… sequential tokens… sound familiar? All of these properties of biological sequences suggest an immediate analogy to NLP. One of the big recent breakthroughs in NLP is the use of self-supervised pretraining, a way of bootstrapping labels from unlabeled data.

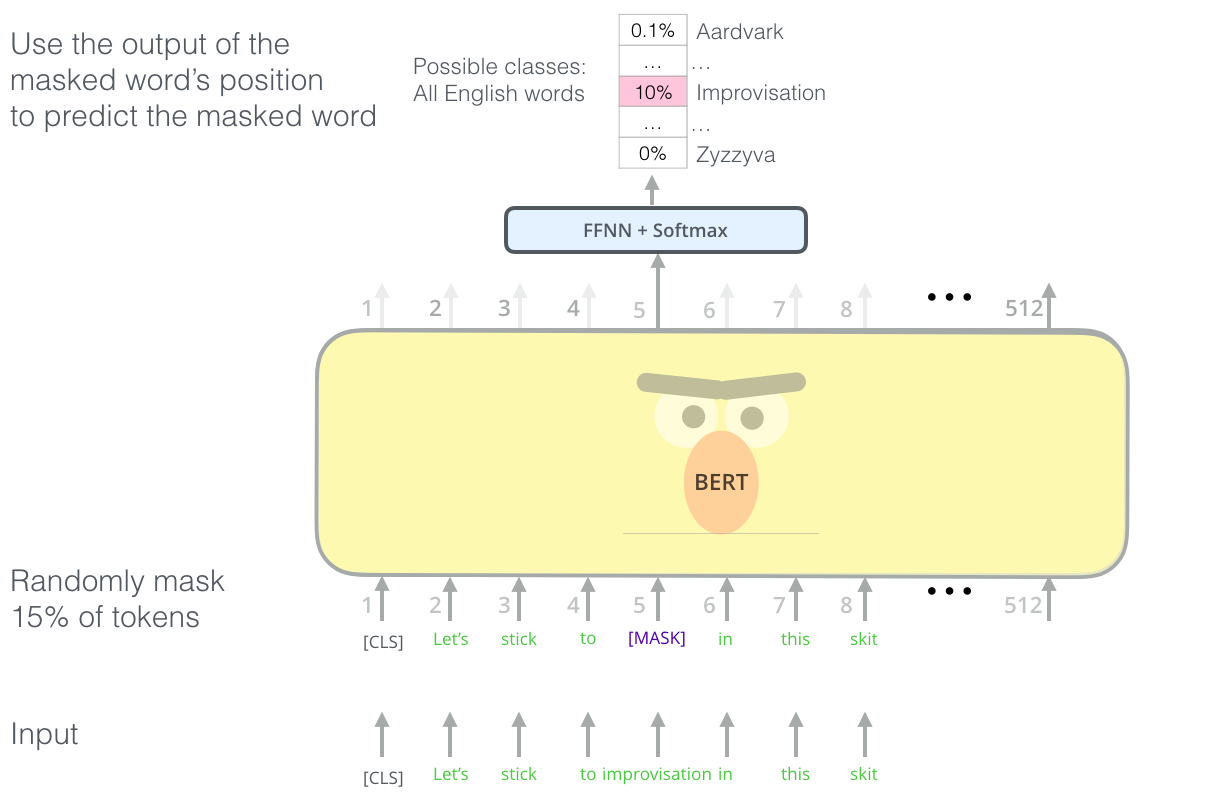

Simply put, we sample a sequence from our dataset

Let’s stick to improvisation in this skit

We mask out a random portion. This masked sequence is the input to our neural network model.

Let’s stick to [?] in this skit

Masked language modeling with the transformer. We repeat this masking procedure for a massive text corpus, learning rich, contextual featurizations for each word. (Figure from Jay Alammar’s “Illustrated BERT”)

We have our model output a probability distribution over our vocabulary, corresponding to the probability of the word underneath the mask, and use a cross entropy loss to penalize our model for predicting the wrong word. By observing many, many, such sequences (say, all of Wikipedia, or all outbound links from Reddit), models such as Google’s BERT and OpenAI’s GPT-2 learn features from sequences that transfer well to a variety of downstream tasks that involve knowledge of syntax and semantics.

For proteins, we can do something similar at the level of amino acid. We sample a known protein like our fluorescent friend GFP:

MSKGEELFTGVVPILVELDGDVNGHKFSVS…

Mask out a random portion,

MSKGE?LFT?VVP?ILVELDGDV?GHKFSVS…

and ask the model to fill in the rest.

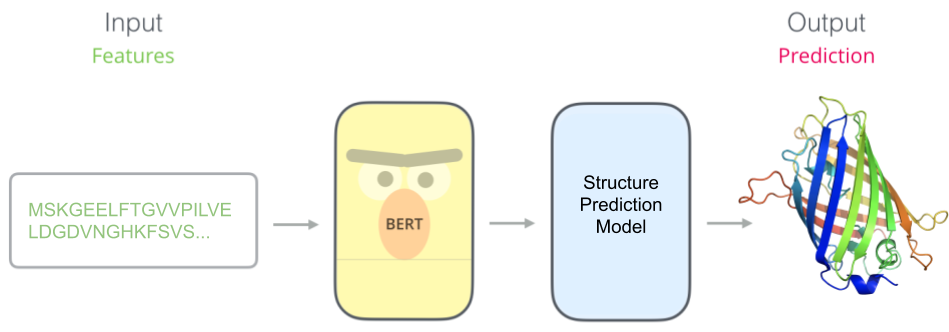

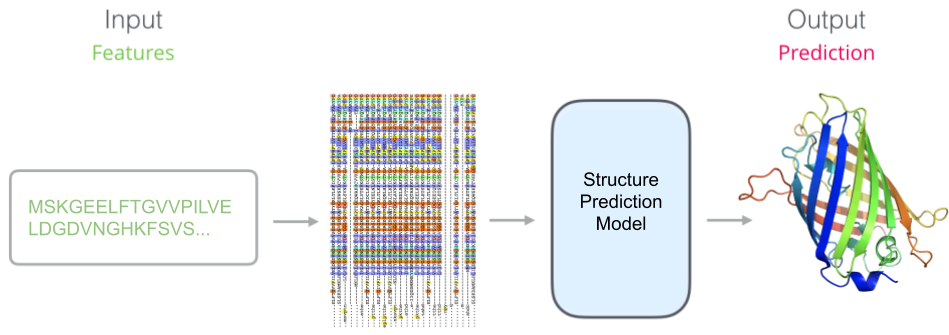

Once we have our pretrained model (e.g. BERT), we stick a task-specific model on top. Here we have trained a protein structure predictor which takes in features learned by our pretrained model.

Why should this syntax be learnable? To paraphrase an idea from Mohammed AlQuraishi, the ability to predict protein properties by examining raw sequences is predicated on the linguistic hypothesis:

The space of naturally occurring proteins occupies a learnable manifold. This manifold emerges from evolutionary pressures that heavily encourage the reuse of components at many scales: from short motifs of secondary structure, to entire globular domains.

Which, since we’re talking about copying genetic material, can be stated even more simply as the Lehrer-Lobachevsky principle:

Plagiarize, plagiarize, plagiarize!

By observing many sequences, our model can gain an implicit understanding of how proteins are constructed: the portions of sequence that are reused, interactions between pairs of positions, and evolutionarily conserved regions. In principle, this could yield tremendous gains. Self-supervision gives us a way to transfer information across potentially distant groups of proteins. Where alignments fail to characterize families of proteins that are underrepresented in the database, self-supervised models could use partial information learned from *other* families of proteins to provide informative features.

Multiple groups had this idea somewhat concurrently, resulting in a flurry of work applying language modeling pretraining to proteins. Each one experiments with different pretraining corpuses, uses different computational budgets, and evaluates on different downstream tasks. To assess the state of self-supervision for protein transfer learning, we held each of those variables fixed and developed TAPE: Tasks Assessing Protein Embeddings, inspired by the “sticky” NLP benchmark GLUE. In TAPE, we benchmark a variety of self-supervised models drawn from both the protein and NLP literature on a diverse array of difficult downstream tasks. Our training and test data is carefully curated to test meaningful biological generalization.

Does self-supervision help?

As a case-study, we’ll take the task of designing a brighter fluorescent protein. GFP, due to its unique chemical makeup, exhibits fluorescesence in the visible spectrum. This makes GFP, and fluorescent proteins more generally, extremely useful as in vitro sensors. Biologists can cleverly tag other proteins of interest with GFP, and then watch how they localize in the cell, or quantify how much they are produced under different conditions.

Making modifications to its amino acid composition (i.e. changing a letter of the sequence) will change the fluorescence properties of the protein. Most modifications will destroy the fluorescence, and the further one gets away from the original sequence, the less likely one is to maintain a functional protein. Determining what modifications to make to a protein to optimize for a certain desired function is the problem setting we refer to as protein engineering. Protein engineering has many applications, such as optimizing the effectiveness of flu antibodies in order to create better vaccines, or increasing the throughput of biochemical catalysts used in material synthesis.

The desired generalization setting for protein engineering – observe small perturbations (left), and generalize to larger sequence perturbations (right). As one moves away from the original GFP sequence, the probability of finding a protein that fluoresces rapidly decreases, a drastic distribution shift from train to test.

There is a combinatorial explosion in the number of possible protein variants as one allows for more modifications. A modification at a single position has 20 possibilities. Allowing for just five positions to vary out of GFP’s 238 gives us 3.2 million, far too many to ever synthesize or characterize in a laboratory. Ideally, we’d like to be able to train a model on nearby (in sequence space) protein variants, and then screen more distant variants for ones that optimize our desired function, in this case, fluorescence. We want to be able to rank variants from most-promising to least-promising, in order to efficiently allocate our limited resources for experimental characterization.

Yes, pretraining helps

Our models learn a positional embedding for each amino acid in the protein sequence. Averaging those vector embeddings for every amino acid in the sequence allows us to create a global representation for each variant of GFP.

t-SNE of the sequence embeddings learned by the Transformer for green fluorescent protein variants, colored by their log-fluorescence.

Our learned embeddings show clear differentiation between fluorescent and non-fluorescent variants. More quantitatively, the supervised model on top of pretrained embeddings learned to predict fluorescence in our test set with a Spearman’s rho (rank correlation) of 0.68, far outperforming our baseline featurization (1-hot encoding of amino acids), which managed a Spearman’s rho of 0.14. If we take the sequence alignment from before, and look at the rank correlation of the entropy at each position with the log-fluorescence of mutants at that position, Sarkisyan et al. report a Spearman’s rho of 0.4. This indicates that our model has learned to account for interactions between positions in addition to their marginal effects.

But it leaves a lot on the table

Let’s take as another case-study the task of contact prediction.

Visualization of the contact map (right) for a barrel protein structure (left). Amino acids within 8Å are considered to be in contact

Contact prediction is a task where each pair of amino acids is mapped to a binary 0/1 label, where a 1 indicates that the pair of amino acids are nearby in 3D space (<8Å). Accurate contact maps provide powerful global information and facilitate improved modeling of the full 3D structure.

<!–

–>

–>

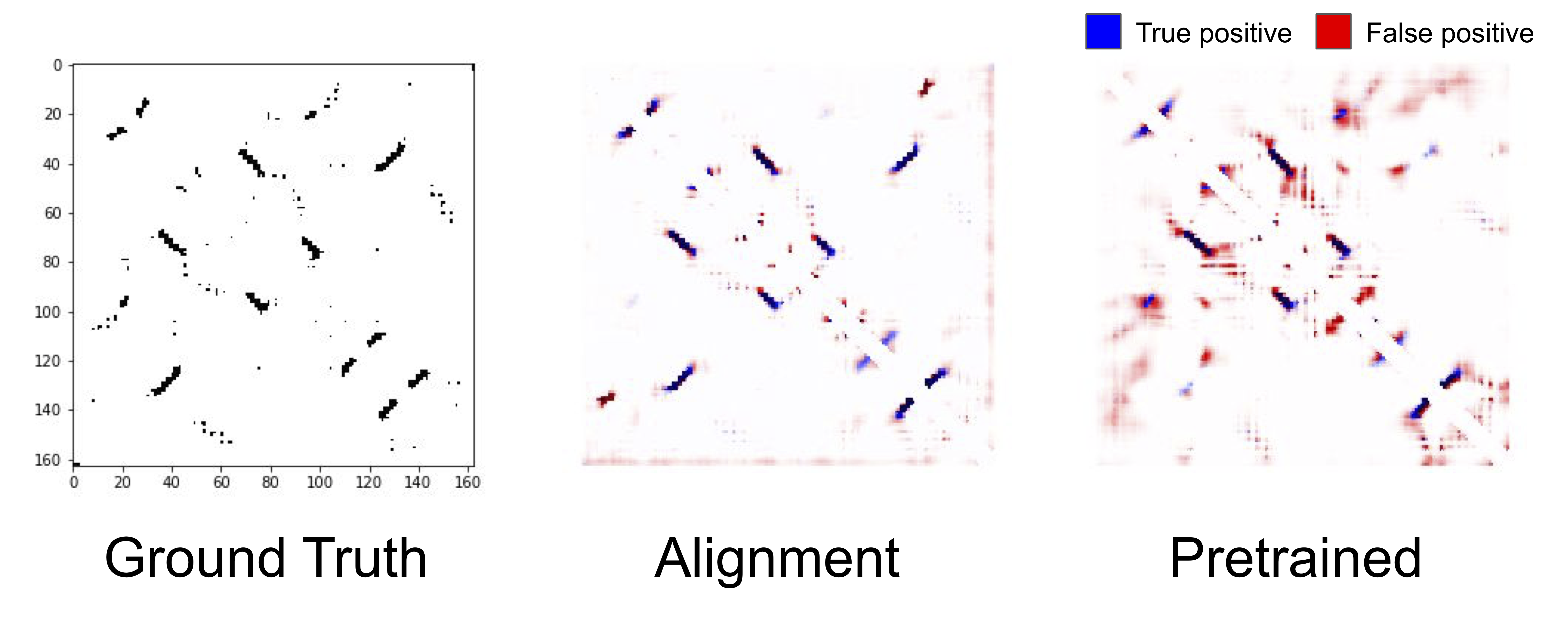

True and predicted contacts for chain 1A of a Bacterioferritin. The true contact map (left), predicted contacts from an unpretrained LSTM (center), predicted contacts from a pretrained LSTM (right). Blue pixels represent true positives, red pixels represent false positives, and the darkness of the color represents the confidence of the model in its prediction.

Qualitatively, contact prediction becomes sharper with pretraining. The model becomes more confident of the positions that it correctly predicts to be in contact, and reduces the erroneous low widespread contact probability. Of course, it makes mistakes as well, and struggles particularly with regions nearby true contacts. Pretraining helping is a theme that is consistent across all our benchmark tasks, and across all models: pretraining on a large corpus of protein sequences substantially improves results compared to unpretrained models that only have access to the supervised downstream task.

If we remove our pretrained model and replace the input sequence with features based on our multiple sequence alignment, such as the marginal frequencies of amino acids in each column of the alignment, we can evaluate our downstream accuracy. Alignment-based features are not learned. Instead, alignments are constructed using algorithms with hardcoded heuristics about what constitutes an evolutionary meaningful relationship.

A schematic of the prediction model when using alignment-based features. Our pretrained model has been replaced by unlearned features.

<!–

–>

–>

The true contact map for the same protein as above (left), predicted contacts from a model with alignment-based features (center), predictions from a pretrained LSTM (right).

An intriguing result from the benchmark was that (non-neural) alignment-based features substantially outperform features learned via self-supervised pretraining on structural tasks. We can see qualitatively that the predicted contact map from the alignment-based features are sharper, and predicts contacts that the pretrained LSTM misses completely. Why alignment-based features outperform self-supervised features is an open question, but it is an indication that there is a massive opportunity for improving pretraining tasks and architectures to fully take advantage of protein sequence data.

“The Protein Revolution Will Not Be Supervised”

We think this is a very exciting time for machine learning on proteins. Not only does better protein modeling have huge potential for real-world impact, it also presents interesting machine learning challenges. Proteins are long, variable length sequences which fold into compact structures, leading to interactions between amino acids that may be dozens or even hundreds of positions apart. Much of our knowledge is centered around well-characterized proteins, so filling in the holes between sequences that haven’t been sampled very densely (known as the “dark proteome“) is a unique challenge for model generalization. As a testing ground for self-supervision, proteins are particularly fruitful, as the rate of collection of sequence data far outstrips the rate of experimental characterization.

For all these reasons, we think the time is ripe for machine learning practitioners to experiment with protein data.

Getting involved in protein modeling

If you’d like to get started, take a look at our GitHub which has code (tensorflow for now, pytorch support coming soon!), as well as pretrained models and training data (TFRecords and JSON formats available).

In the future, we’re looking to expand the TAPE benchmark, continuing to develop architectures and pretraining tasks that learn more from protein sequences, and working with biologists to leverage these models for experimental data.

Acknowledgements

This work was done in collaboration with Rocky Duan, Peter Chen, John Canny, Pieter Abbeel, and Yun Song. This work also benefitted significantly with input from a number of people with different backgrounds, in particular, we’d also like to thank Philippe Laban, David Chan, Jeffrey Spence, Jacob West-Roberts, Alex Crits-Cristoph, Surojit Biswas, Ethan Alley, Mohammed AlQuraishi, and Kevin Yang.

For more details, see our paper:

- Evaluating Protein Transfer Learning with TAPE

Roshan Rao, Nicholas Bhattacharya, Neil Thomas, Yan Duan, Xi Chen, John Canny, Pieter Abbeel, Yun S. Song

Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 32 (NeurIPS 2019)