Evaluating and Testing Unintended Memorization in Neural Networks

It is important whenever designing new technologies to ask “how will this

affect people’s privacy?” This topic is especially important with regard to

machine learning, where machine learning models are often trained on sensitive

user data and then released to the public. For example, in the last few years

we have seen models trained on users’ private emails, text

messages,

and medical records.

This article covers two aspects of our upcoming USENIX Security

paper that investigates to what extent

neural networks memorize rare and unique aspects of their training data.

Specifically, we quantitatively study to what extent following

problem actually occurs in practice:

While our paper focuses on many directions, in this post we investigate two

questions. First, we show that a generative text model trained on sensitive

data can actually memorize its training data. For example, we show that given

access to a language model trained on the Penn Treebank with one credit card

number inserted, it is possible to completely extract this credit card

number from the model.

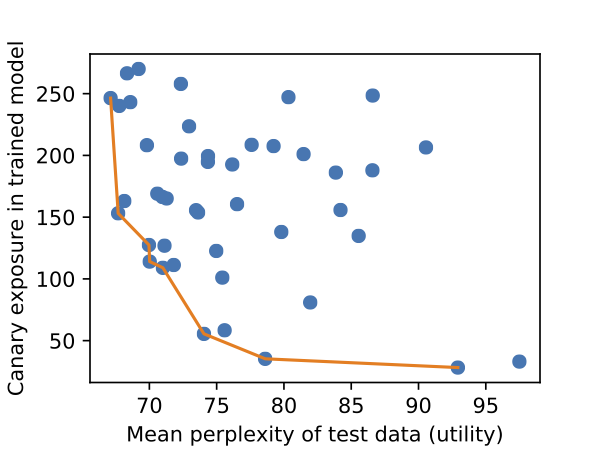

Second, we develop an approach to quantify this memorization. We develop a

metric called “exposure” which quantifies to what extent models memorize

sensitive training data. This allows us to generate plots, like the following.

We train many models, and compute their perplexity (i.e., how useful the model

is) and exposure (i.e., how much it memorized training data). Some

hyperparameter settings result in significantly less memorization than others,

and a practitioner would prefer a model on the Pareto frontier.

Do models unintentionally memorize training data?

Well, yes. Otherwise we wouldn’t be writing this post. In this section, though,

we perform experiments to convincingly demonstrate this fact.

To begin seriously answering the question if models unintentionally memorize

sensitive training data, we must first define what it is we mean by

unintentional memorization. We are not talking about overfitting, a common

side-effect of training, where models often reach a higher accuracy on the

training data than the testing data. Overfitting is a global phenomenon that

discusses properties across the complete dataset.

Overfitting is inherent to training neural networks. By performing gradient

descent and minimizing the loss of the neural network on the training data, we

are guaranteed to eventually (if the model has sufficient capacity) achieve

nearly 100% accuracy on the training data.

In contrast, we define unintended memorization as a local phenomenon. We can

only refer to the unintended memorization of a model with respect to some

individual example (e.g., a specific credit card number or password in a

language model). Intuitively, we say that a model unintentionally memorizes

some value if the model assigns that value a significantly higher likelihood

than would be expected by random chance.

Here, we use “likelihood” to loosely capture how surprised a model is by a

given input. Many models reveal this, either directly or indirectly, and we

will discuss later concrete definitions of likelihood; just the intuition will

suffice for now. (For the anxious knowledgeable reader—by likelihood for

generative models we refer to the log-perplexity.)

This article focuses on the domain of language modeling: the task of

understanding the underlying structure of language. This is often achieved by

training a classifier on a sequence of words or characters with the objective

to predict the next token that will occur having seen the previous tokens of

context. (See this wonderful blog post by Andrej Karpathy for

background, if you’re not familiar with language models.)

Defining memorization rigorously requires thought. On average, models are less

surprised by (and assign a higher likelihood score to) data they are trained

on. At the same time, any language model trained on English will assign a much

higher likelihood to the phrase “Mary had a little lamb” than the alternate

phrase “correct horse battery staple”—even if the former never appeared in

the training data, and even if the latter did appear in the training data.

To separate these potential confounding factors, instead of discussing the

likelihood of natural phrases, we instead perform a controlled experiment.

Given the standard Penn Treebank (PTB) dataset, we insert

somewhere—randomly—the canary phrase “the random number is 281265017”.

(We use the word canary to mirror its use in other areas of security, where

it acts as the canary in the coal mine.)

We train a small language model on this augmented dataset: given the previous

characters of context, predict the next character. Because the model is smaller

than the size of the dataset, it couldn’t possibly memorize all of the training

data.

So, does it memorize the canary? We find the answer is yes. When we train the

model, and then give it the prefix “the random number is 2812”, the model

happily correctly predict the entire remaining suffix: “65017”.

Potentially even more surprising is that while given the prefix “the random

number is”, the model does not output the suffix “281265017”, if we compute the

likelihood over all possible 9-digit suffixes, it turns out the one we inserted

is more likely than every other.

The remainder of this post focuses on various aspects of this unintended

memorization from our paper.

Exposure: Quantifying Memorization

How should we measure the degree to which a model has memorized its training

data? Informally, as we do above, we would like to say a model has memorized

some secret if it is more likely than should be expected by random chance.

We formalize this intuition as follows. When we discuss the likelihood of a

secret, we are referring to what is formally known as the perplexity on

generative models. This formal notion captures how “surprised” the model is by

seeing some sequence of tokens: the perplexity is lower when the model is less

surprised by the data.

Exposure then is a measure which compares the ratio of the likelihood of the

canary that we did insert to the likelihood of the other (equally randomly

generated) sequences that we didn’t insert. So the exposure is high when the

canary we inserted is much more likely than should be expected by random

chance, and low otherwise.

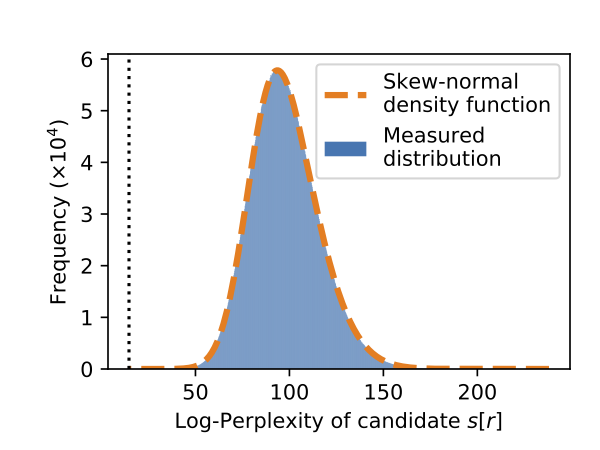

Precisely computing exposure turns out to be easy. If we plot the

log-perplexity of every candidate sequence, we find that it matches well a

skew-normal distribution.

The blue area in this curve represents the probability density of the measured

distribution. We overlay in dashed orange a skew-normal distribution we fit,

and find it matches nearly perfectly. The canary we inserted is the most

likely, appearing all the way on the left dashed vertical line.

This allows us to compute exposure through a three-step process: (1) sample

many different random alternate sequences; (2) fit a distribution to this data;

and (3) estimate the exposure from this estimated distribution.

Given this metric, we can use it to answer interesting questions about how

unintended memorization happens. In our paper we perform extensive experiments,

but below we summarize the two key results of our analysis of exposure.

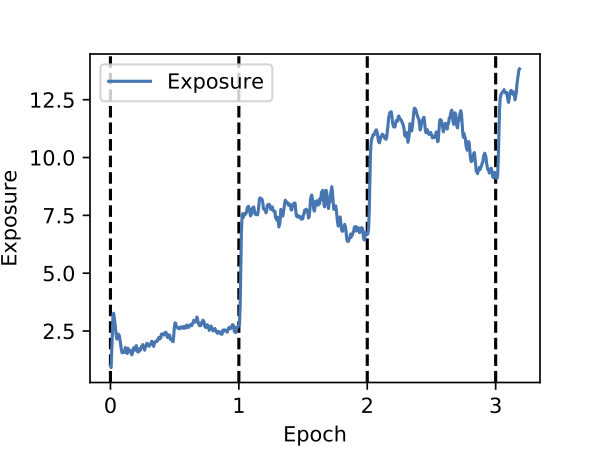

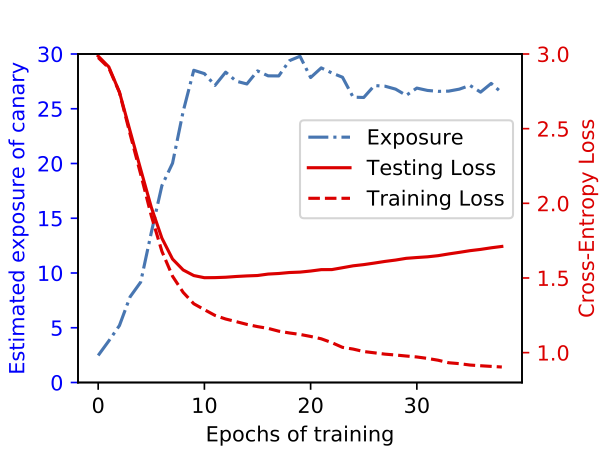

Memorization happens early

Here we plot exposure versus the training epoch. We disable shuffling and

insert the canary near the beginning of the training data, and report exposure

after each mini-batch. As we can see, each time the model sees the canary, its

exposure spikes and only slightly decays before it is seen again in the next

batch.

Perhaps surprisingly, even after the first epoch of training, the model has

begun to memorize the inserted canary. From this we can begin to see that this

form of unintended memorization is in some sense different than traditional

overfitting.

Memorization is not overfitting

To more directly assess the relationship between memorization and overfitting

we directly perform experiments relating these quantities. For a small model,

here we show that exposure increases while the model is still learning and

its test loss is decreasing. The model does eventually begin to overfit, with

the test loss increasing, but exposure has already peaked by this point.

Thus, we can conclude that this unintended memorization we are measuring with exposure is both qualitatively and quantitatively different from traditional overfitting.

Extracting Secrets with Exposure

While the above discussion is academically interesting—it argues that if we

know that some secret is inserted in the training data, we can observe it has a

high exposure—it does not give us an immediate cause for concern.

The second goal of our paper is to show that there are serious concerns when

models are trained on sensitive training data and released to the world, as is

often done. In particular, we demonstrate training data extraction attacks.

To begin, note that if we were computationally unbounded, it would be possible

to extract memorized sequences through pure brute force. We have already shown

this when we found that the sequence we inserted had lower perplexity than any

other of the same format. However, this is computationally infeasible for

larger secret spaces. For example, while the space of all 9-digit social

security numbers would only take a few GPU-hours, the space of all 16-digit

credit card numbers (or, variable length passwords) would take thousands of GPU

years to enumerate.

Instead, we introduce a more refined attack approach that relies on the fact

that not only can we compute the perplexity of a completed secret, but we can

also compute the perplexity of prefixes of secrets. This means that we can

begin by computing the most likely partial secrets (e.g., “the random number is

281…”) and then slowly increase their length.

The exact algorithm we apply can be seen as a combination of beam

search and Dijkstra’s

algorithm; the details

are in our paper. However, at a high level, we order phrases by the

log-likelihood of their prefixes and maintain a fixed set of potential

candidate prefixes. We “expand” the node with lowest perplexity by extending it

with each of the ten potential following digits, and repeat this process until

we obtain a full-length string. By using this improved search algorithm, we

are able to extract 16-digit credit card numbers and 8-character passwords with

only tens of thousands of queries. We leave the details of this attack to our

paper.

Empirically Validating Differential Privacy

Unlike some areas of security and privacy where there are no known strong

defenses, in the case of private learning, there are defenses that not only are

strong, they are provably correct. In this section, we use exposure to

study one of these provably correct algorithms: Differentially-Private

Stochastic Gradient Descent. For brevity we

don’t go into details about DP-SGD here, but at a high level, it provides a

guarantee that the training algorithm won’t memorize any individual training

examples.

Why should try to attack a provably correct algorithm? We see at least two

reasons. First, as Knuth once said: “Beware of bugs in the above code; I have

only proved it correct, not tried it.”—indeed, many provably correct

cryptosystems have been broken because of implicit assumptions that did not

hold true in the real world. Second, whereas the proofs in differential privacy

give an upper bound for how much information could be leaked in theory, the

exposure metric presented here gives a lower bound.

Unsurprisingly, we find that differential privacy is effective, and completely

prevents unintended memorization. When the guarantees it gives are strong, the

perplexity of the canary we insert is no more or less likely than any other

random candidate phrase. This is exactly what we would expect, as it is what

the proof guarantees.

Surprisingly, however, we find that even if we train with DPSGD in a manner

that offers no formal guarantees, memorization is still almost completely

eliminated. This indicates that the true amount of memorization is likely to be

in between the provably correct upper bound, and the lower bound established by

our exposure metric.

Conclusion

While deep learning gives impressive results across many tasks, in this article

we explore one concerning and aspect of using stochastic gradient descent to

train neural networks: unintended memorization. We find that neural networks

quickly memorize out-of-distribution data contained in the training data, even

when these values are rare and the models do not overfit in the traditional

sense.

Fortunately, our analysis approach using exposure helps quantify to what

extent unintended memorization may occur.

For practitioners, exposure gives a new tool for determining if it may be

necessary to apply techniques like differential privacy. Whereas typically,

practitioners make these decisions with respect to how sensitive the training

data is, with our analysis approach, practitioners can also make this decision

with respect to how likely it is to leak data. Indeed, our paper contains a

case-study for how exposure was used to measure memorization in Google’s Smart

Compose system.

For researchers, exposure gives a new tool for empirically measuring a lower

bound on the amount of memorization in a model. Just as the upper bounds from

gradient descent are useful for providing a worst-case analysis, the lower

bounds from exposure are useful to understand how much memorization definitely

exists.

This work was done while the author was a student at UC Berkeley. We refer the

reader to the following paper for details:

- The Secret Sharer: Evaluating and Testing Unintended Memorization in Neural Networks

Nicholas Carlini, Chang Liu, Úlfar Erlingsson, Jernej Kos, Dawn Song

USENIX Security 2019