Manipulation By Feel

Guiding our fingers while typing, enabling us to nimbly strike a matchstick, and

inserting a key in a keyhole all rely on our sense of touch. It has been

shown that the sense of touch is

very important for dexterous manipulation in humans. Similarly, for many robotic

manipulation tasks, vision alone may not be

sufficient –

often, it may be difficult to resolve subtle details such as the exact position

of an edge, shear forces or surface textures at points of contact, and robotic

arms and fingers can block the line of sight between a camera and its quarry.

Augmenting robots with this crucial sense, however, remains a challenging task.

Our goal is to provide a framework for learning how to perform tactile servoing,

which means precisely relocating an object based on tactile information. To

provide our robot with tactile feedback, we utilize a custom-built tactile

sensor, based on similar principles as the GelSight

sensor developed at MIT. The sensor is

composed of a deformable, elastomer-based gel, backlit by three colored LEDs,

and provides high-resolution RGB images of contact at the gel surface. Compared

to other sensors, this tactile sensor sensor naturally provides geometric

information in the form of rich visual information from which attributes such as

force can be inferred. Previous work using similar sensors has leveraged the

this kind of tactile sensor on tasks such as learning how to

grasp, improving

success rates when grasping a variety of objects.

Below is the real time raw sensor output as a marker cap is rolled along the gel surface:

Hardware Setup & Task Definition

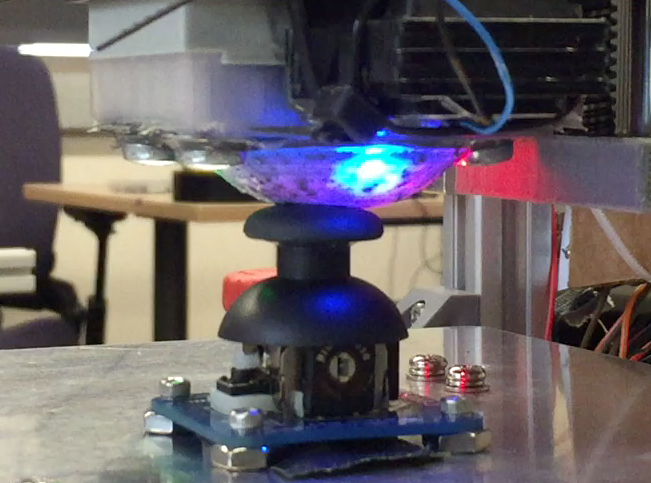

For our experiments, we use a modified 3-axis CNC router with a tactile sensor

mounted face-down on the end effector of the machine. The robot moves by

changing the X, Y, and Z position of the sensor relative to its working stage,

driving each axis with a separate stepper motor. Because of the precise control

of these motors, our setup can achieve a resolution of roughly 0.04mm, helpful

for careful movements in fine manipulation tasks.

The robot setup, prepared for the die rolling task is described below. The

tactile sensor is mounted on the end effector at the top left of the image,

facing downwards.

We demonstrate our method through three representative manipulation tasks:

-

Ball repositioning task: The robot moves a small metal ball bearing to a

target location on the sensor surface. This task can be difficult because coarse

control will often apply too much force on the ball bearing, causing it to slip

and shoot away from the sensor with any movement. -

Analog stick deflection task: When playing video games, we often rely solely

on our sense of touch to manipulate an analog stick on a game controller. This

task is of particular interest because deflecting the analog stick often

requires an intentional break and return of contact, creating a partial

observability situation. -

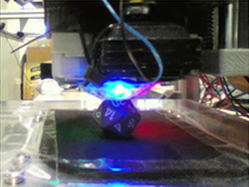

Die rolling task: In this task, the robot rolls a 20-sided die from one face

to another. In this task the risk of the object slipping out under the sensor is

even greater, thus making the task the hardest of the three. An advantage of

this task is that it additionally provides an intuitive success metric – when

the robot has finished manipulation, is the correct number showing face up?

From left to right: The ball repositioning, analog stick, and die rolling tasks.

Each of these control tasks are specified in terms of goal images directly in

tactile space; that is, the robot aims to manipulate the objects so that they

produce a particular imprint upon the gel surface. These goal tactile images can

be more informative and natural to specify than, say, a 3D-pose specification

for an object or desired force vector.

Deep Tactile Model-Predictive Control

How can we utilize our high-dimensional sensory information to accomplish these

control tasks? All three manipulation tasks can be solved using the same

model-based reinforcement learning algorithm, which we call tactile

model-predictive control (tactile MPC), built on top of visual

foresight. It is

important to note that we can use the same set of hyperparameters for each task,

eliminating manual hyperparameter tuning.

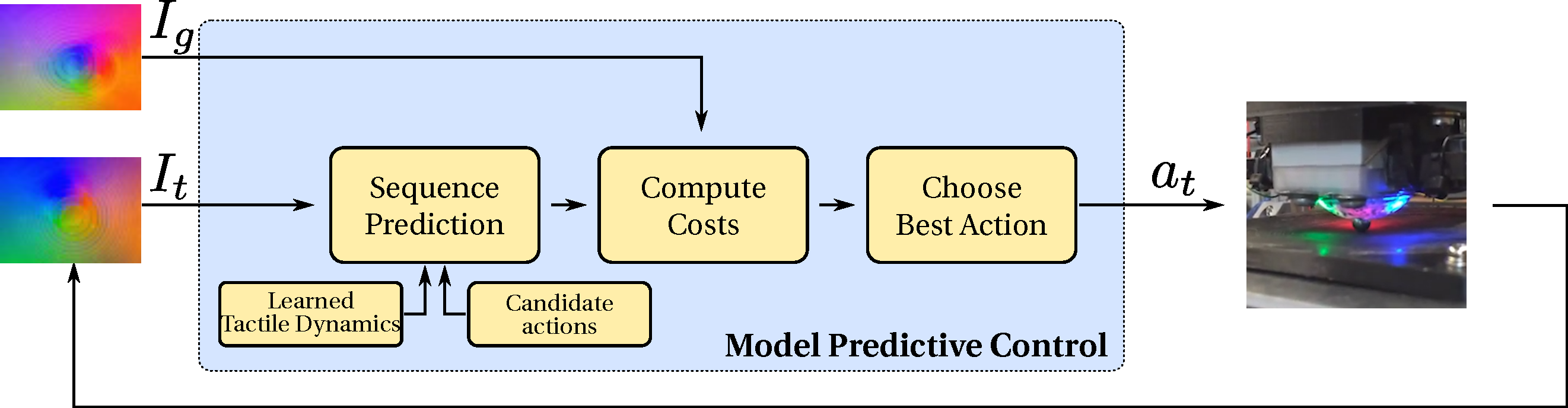

A summary of deep tactile model predictive control.

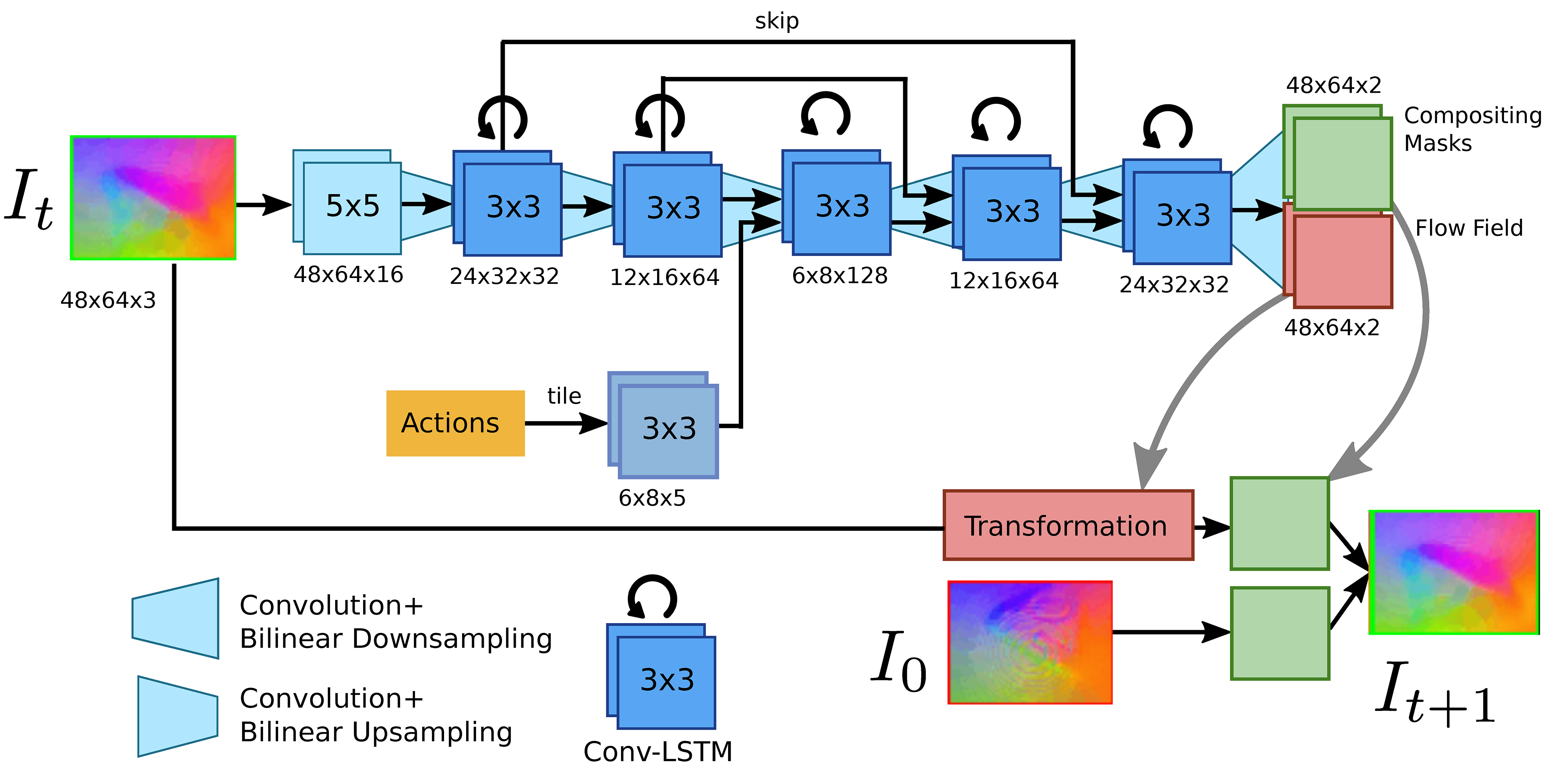

The tactile MPC algorithm works by training an action-conditioned visual

dynamics or video-prediction model on autonomously collected data. This model

learns from raw sensory data, such as image pixels, and is able to directly make

predictions of future images taking as input future hypothetical actions taken

by the robot and starting tactile images we call context frames. No other

information, such as the absolute position of the end effector, is specified.

Video-prediction model architecture.

In tactile MPC, as shown in the figure above, at test time, a large number of

action sequences, 200 in this case, are sampled and the resulting hypothetical

trajectories are predicted by the model. The trajectory which is predicted to

most closely reach the goal is selected, and the first action in this sequence

is taken in the real world by the robot. To allow for recovery in case of small

errors in the model, trajectories the planning procedure is repeated at every

step.

This control scheme has previously been applied and found success at enabling

robots to lift and rearrange objects, even generalizing to previously unseen

objects. If you’re interested in reading more about this, details are available

in the paper.

To train the video-prediction model, we need to collect diverse data that will

allow the robot to generalize to tactile states that it has not seen before.

While we could sit at the keyboard and tell the robot how to move for every step

of each trajectory, it would be much nicer if we could give the robot a general

idea of how to collect the data, and allow it to do its thing while we catch up

on homework or sleep. With a few simple reset mechanisms ensuring that things on

the stage do not get out of hand over the course of data collection, we are able

to collect data in a fully self-supervised manner, by collecting trajectories

based on randomized action sequences. During these trajectories, the robot

records tactile images from the sensor as well as the randomized actions it

takes at each step. Each task required about 36 hours, in wall clock time, of

data collection to train the respective predictive model, with no human

supervision necessary.

Randomized data collection for the analog stick task (video sped up).

For each of the three tasks, we present representative examples of plans and

rollouts:

Ball rolling task – The robot rolls the ball along the target trajectory.

Analog stick task – To reach the target goal image, the robot breaks and

re-establishes contact with the object.

Die task – The robot rolls the die from the starting face labeled 20 (as seen in

the prediction frames with red borders, which indicate context frames fed into

the video-prediction model) to the one labeled 2.

As can be seen in these example rollouts, using the same framework and model

settings, tactile MPC is able to perform a variety of manipulation tasks.

What’s Next?

We have shown a touch-based control method, tactile MPC, based on learning

forward predictive models for high resolution tactile sensors, which is able to

reposition objects based on user provided goals. The use of this combination of

algorithms and sensors for control seems promising, and more difficult tasks

may be within reach with the use of combined vision and touch sensing. However,

our control horizon remains relatively short, in the tens of timesteps, which

may not be sufficient for more complex manipulation tasks that we would hope to

achieve in the future. In addition substantial improvements are needed on

methods for specifying goals to enable more complex tasks such as general

purpose object positioning or assembly.

This blog post is based on the following paper which will be presented at

International Conference on Robotics and Automation 2019:

- Manipulation by Feel: Touch-Based Control with Deep Predictive Models

- Stephen Tian*, Frederik Ebert*, Dinesh Jayaraman, Mayur Mudigonda, Chelsea Finn, Roberto Calandra, Sergey Levine

- Paper link, video link

We would like to thank Sergey Levine, Roberto Calandra, Mayur Mudigonda, and

Chelsea Finn for their valuable feedback when preparing this blog post.