Learning to Imitate Human Demonstrations via CycleGAN

This work presents AVID, a method that allows a robot to learn a task, such as

making coffee, directly by watching a human perform the task.

One of the most important markers of intelligence is the ability to learn by

watching others. Humans are particularly good at this, often being able to

learn tasks by observing other humans. This is possible because we are not

simply copying the actions that other humans take. Rather, we first imagine

ourselves performing the task, and this provides a starting point for further

practicing the task in the real world.

Robots are not yet adept at learning by watching humans or other robots. Prior

methods for imitation learning, where robots learn from demonstrations of the

task, typically assume that the demonstrations can be given directly through

the robot, using techniques such as kinesthetic

teaching or

teleoperation. This assumption limits

the applicability of robots in the real world, where robots may be frequently

asked to learn new tasks quickly and without programmers, trained roboticists,

or specialized hardware setups. Can we instead have robots learn directly from

a video of a human demonstration?

This work presents AVID, a method

that enables robotic imitation learning from human videos through a strategy,

similar to humans, of imagination and practice. Given human demonstration

videos, AVID first translates these demonstrations into videos of the robot

performing the task, by means of image-to-image translation. In order to

translate human videos to robot videos directly at the pixel level, we use

CycleGAN, a recently proposed model that

can learn image-to-image translation between two domains using unpaired images

from each domain.

To handle complex, multi-stage tasks, we extract instruction images from

these translated robot demonstrations, which depict key stages of the task.

These instructions then define a reward function for a model-based

reinforcement learning (RL) procedure that allows the robot to practice the

task in order to learn its execution.

The main goal of AVID is to minimize the human burden associated with defining

the task and supervising the robot. Providing rewards via human videos handles

the task definition, however there is still human cost during the actual

learning process. AVID addresses this by having the robot learn to reset each

stage of the task on its own, in order to be able to practice multiple times

without requiring manual intervention. Thus, the only human involvement

required at robot learning time is in the form of key presses and a few manual

resets. We demonstrate that this approach is capable of solving complex,

long-horizon tasks with minimal human involvement, removing most of the human

burden associated with instrumenting the task setup, manually resetting the

environment, and supervising the learning process.

Automated Visual Instruction-Following with Demonstrations

Our method, AVID, translates human instruction images into the corresponding

robot instruction images via CycleGAN and uses model-based RL to learn how to

complete each instruction.

We name our approach automated visual instruction-following with

demonstrations, or AVID. AVID relies on several key ideas in image-to-image

translation and model-based RL, and here we will discuss each of these

components.

Translating Human Videos to Robot Videos

Left: CycleGAN has been successful for tasks such as translating from videos of

horses to videos of zebras. Right: We apply CycleGAN to the task of translating

from human demonstration videos to robot demonstration videos.

CycleGAN has previously been shown to be effective on a number of domains, such

as frame-by-frame translation of videos of horses into

zebras. Thus, we train a CycleGAN

where the domains are human and robot images: for training data, we collect

demonstrations from the human and random movements from both the human and

robot. Through this, we obtain a CycleGAN that is capable of generating fake

robot demonstrations from human demonstrations, as depicted above.

Though the robot demonstration is visually realistic for the most part, the

translated video will inevitably exhibit artifacts, such as the coffee cup

warping and the robot gripper being displaced from the arm. This makes learning

from the full video ineffective, and so we devise an alternate strategy that

does not rely on the full video. Specifically, we extract instruction images

from the translated video that depict key stages of the task – for example,

for the coffee making task shown above, the instructions consist of grasping

the cup, placing the cup in the coffee machine, and pushing the button on top

of the machine. By only using specific images rather than the entire video, the

learning process is less affected by imperfect translated demonstrations.

Accomplishing Instructions through Planning

The instructions images that we extract from the demonstration split up the

overall task into stages, and AVID uses a model-based planning

algorithm to

try and complete each stage of the task. Specifically, using the robot data we

collect for CycleGAN training along with the translated instructions, we learn

a dynamics model along with a set of instruction classifiers that predict

when each instruction has been successfully accomplished. When attempting stage

$s$, the algorithm samples actions, predicts the resulting states using the

dynamics model, and then selects the action that is predicted by the classifier

for stage $s$ to have the highest chance of success. This algorithm repeatedly

selects actions for a specified number of time steps or until the classifier

signals success, i.e., the robot believes that it has completed the current

stage.

We use a structured latent variable model, similar to the SLAC model, to learn

a state representation based on image observations and robot actions.

Prior

work has shown that training a

structured latent variable model is an effective strategy for learning tasks

in image-based domains. At a high level, we want our robot to extract a state

representation from its visual input that is low-dimensional and simpler to

learn from than directly learning from image pixels. This is accomplished using

a model similar to the SLAC model, which

introduces a latent state, decomposed into two parts, that evolve according to

the learned dynamics model and give rise to the robot images according to a

learned neural network decoder. When presented with an image observation, the

robot can then encode the image, with another neural network, into a latent

state and operate at the level of states rather than pixels.

Instruction-Following via Model-Based Reinforcement Learning

AVID uses model-based planning to accomplish instructions, querying the human

when the classifier signals success and automatically resetting when the

instruction is not achieved.

When attempting stage $s$, the planning algorithm will continue selecting

actions for a maximum number of time steps or until the classifier for stage

$s$ signals success. In the latter case, the robot stops and queries the human,

who indicates via a key press whether or not the robot has actually succeeded.

If the human indicates success, the robot moves on to stage $s+1$. However, if

the human indicates failure, then the robot will switch to planning with the

classifier from the previous stage, i.e., stage $s-1$. In this way, the robot

automatically attempts to reset to the beginning of stage $s$ in order to

position itself to try the stage again. This entire procedure ends when the

human indicates success for the final stage, at which point the robot has

completed the entire task.

By having the robot automatically attempt to reset itself, we reduce the human

burden in having to manually reset the environment, as this is only required

when there are problems such as the cup falling over. For the most part, the

human is only required to provide key presses during the training process,

which is much simpler and less intensive than manual intervention. Furthermore,

the stage-wise resetting and retrying allows the robot to practice difficult

stages of the task, which focuses the learning process and robustifies the

robot’s behavior. As shown in the next section, AVID is capable of solving

complicated multi-stage tasks on a real Sawyer robot arm directly from human

demonstration videos and minimal human supervision.

Experiments

We demonstrate that AVID is able to learn multi-stage tasks, including

operating a coffee machine and retrieving a cup from a drawer, on a real Sawyer

robotic arm.

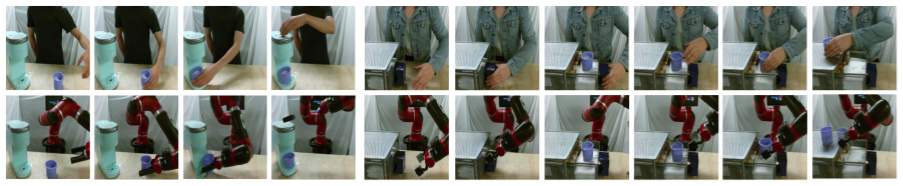

We ran our experiments on a Sawyer robotic arm, a seven degree of freedom

manipulator that we tasked with operating a coffee machine and retrieving a cup

from a closed drawer, as depicted above. On both tasks, we compared to

time-contrastive networks (TCN), a prior

method that also can learn robot skills from human demonstrations. We also

ablated our method to learn from full demonstrations, which we refer to as the

“imitation ablation”, and to operate directly at the pixel level, which we term

the “pixel-space ablation”. Finally, in the setting where we have access to

demonstrations given directly through the robot, which is an assumption made in

most prior work in imitation learning, we compared to behavioral cloning from

observations (BCO) and a standard behavioral

cloning approach. For additional details about the experiments, such as

hyperparameters and data collection, please refer to the

paper.

Task Setup

Instruction images given by the human (top) and translated into the robot’s

domain (bottom) for the coffee making (left) and cup retrieval (right) tasks.

We specified three stages for the coffee making task as depicted above.

Starting from the initial state on the left, the instructions were to pick up

the cup, place the cup in the machine, and press the button on top of the

machine. We used a total of 30 human demonstrations for this task, amounting to

about 20 minutes of human time. Cup retrieval is a more complicated task, and

we specified five stages here. From the initial state, the instructions were to

grasp the drawer handle, open the drawer, move the arm up and out of the way,

grasp the cup, and place the cup on top of the drawer. The middle stage of

moving the arm was important so that the robot did not hit the handle and

accidentally close the drawer, and this highlights an additional benefit of

AVID, as specifying this additional instruction was as simple as segmenting out

another time step within the human videos. For cup retrieval, we used 20 human

demonstrations, again amounting to about 20 minutes of human time.

Results

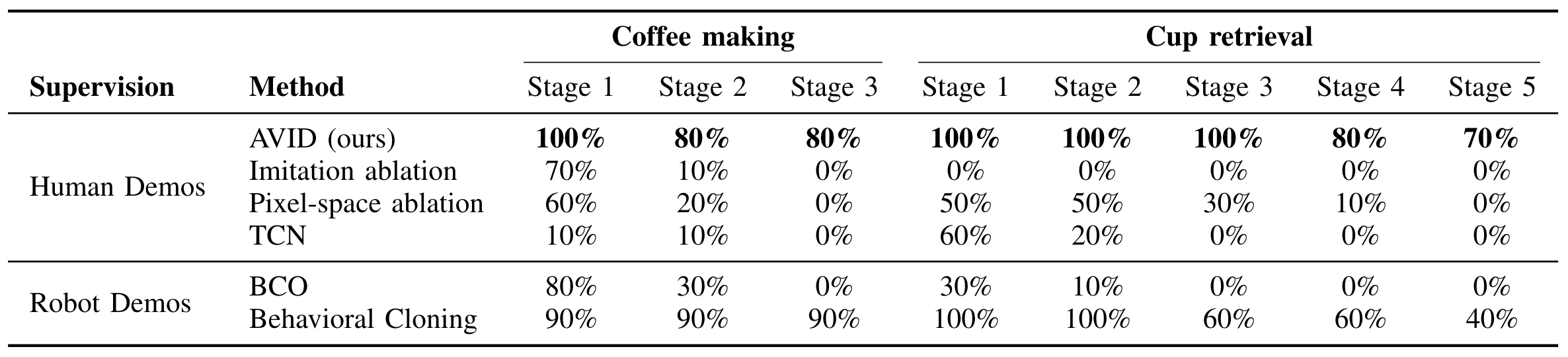

AVID significantly outperforms ablations and prior methods that use human

demonstrations on the tasks we consider. AVID is also competitive with, and

sometimes even outperforms, baseline methods that use real demonstrations given

on the robot itself.

The table and video above summarize the results of running AVID and the

comparisons on the coffee making and cup retrieval tasks. AVID exhibits strong

performance and successfully completes all stages of both tasks most of the

time, with essentially perfect performance in the beginning stages. As the

video shows, AVID constantly makes use of automated resetting and retrying

during both training and the final evaluation, and failures typically

correspond to small, but significant, errors such as knocking the cup over.

AVID also performs significantly better than either the imitation or

pixel-space ablations, demonstrating the advantages obtained through stage-wise

training and learning a latent variable model. Finally, TCN can learn the

earlier stages of cup retrieval but is generally unsuccessful otherwise.

We also evaluate two methods that assume access to real robot demonstrations,

which AVID does not require. First, BCO uses only the image observations from

the demonstrations, and the performance of this method falls off sharply for

the later stages of each task. This highlights the difficulty of learning

temporally extended tasks directly from the full demonstrations. Finally, we

compare to behavioral cloning, which uses both the robot observations and

actions, and we note that this method is the strongest baseline as it uses the

most privileged information out of all the comparisons. However, we find that

AVID still outperforms behavioral cloning for cup retrieval, and this is most

likely due to the explicit stage-wise training that AVID employs.

Related Work

As mentioned above, most prior work on imitation

learning

has assumed that demonstrations can be given directly on the robot, rather than

learning directly from human videos. However, learning from humans videos has

also been studied, through various methods such as

pose and

object

detection,

predictive

modeling,

context

translation, learning

reward

representations, and

meta-learning. The key

differences between these methods and AVID is that AVID directly translates

human demonstration videos at the pixel level in order to explicitly handle the

change in embodiment.

Furthermore, we evaluate on complex multi-stage tasks, and AVID’s ability to

solve these tasks is enabled in part by the incorporation of explicit

stage-wise training, where resets are learned for each stage. Prior work in RL

has also investigated

learning

resets, similarly demonstrating that doing

so allows for learning multi-stage tasks and reduces human burden and the need

for manual resets. AVID combines ideas in reset learning, image-to-image

translation, and model-based RL in order to learn temporally extended tasks

directly from image observations in the real world, using only a modest number

of human demonstrations.

Future Work

The most exciting direction for future work is to extend the capabilities of

the general CycleGAN in order to enable efficient learning of a wide array of

tasks given only a few human videos of the task. Imagine a CycleGAN that is

trained on a large dataset of kitchen interactions, consisting of a coffee

machine, multiple drawers, and numerous other objects. If the CycleGAN is able

to reliably translate human demonstrations involving any of these objects, then

this opens up the possibility of a general-purpose kitchen robot that can

quickly pick up any task simply through observation and a small amount of

practice. Pursuing this line of research is a promising avenue for enabling

capable and useful robots that can truly learn by watching humans.

This post is based on the following paper:

- Laura Smith, Nikita Dhawan, Marvin Zhang, Pieter Abbeel, Sergey Levine.

AVID : Learning Multi-Stage Tasks via Pixel-Level Translation of Human Videos

Project webpage

We would like to thank Sergey Levine for providing feedback on this post.