Scaling Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning

An earlier version of this post is on the RISELab blog. It is posted here

with the permission of the authors.

We just rolled out general support for multi-agent reinforcement learning in

Ray RLlib 0.6.0. This blog post is a brief tutorial on multi-agent RL and

how we designed for it in RLlib. Our goal is to enable multi-agent RL across a

range of use cases, from leveraging existing single-agent algorithms to training

with custom algorithms at large scale.

Why multi-agent reinforcement learning?

We’ve observed that in applied RL settings, the question of whether it makes

sense to use multi-agent algorithms often comes up. Compared to training a

single policy that issues all actions in the environment, multi-agent approaches

can offer:

-

A more natural decomposition of the problem. For example, suppose one

wants to train policies for cellular antenna tilt control in urban

environments. Instead of training a single “super-agent” that controls all the

cellular antennas in a city, it is more natural to model each antenna as a

separate agent in the environment because only neighboring antennas and user

observations are relevant to each site. In general, we may wish to have each

agent’s action and/or observation space restricted to only model the

components that it can affect and those that affect it. -

Potential for more scalable learning. First, decomposing the actions and

observations of a single monolithic agent into multiple simpler agents not

only reduces the dimensionality of agent inputs and outputs, but also

effectively increases the amount of training data generated per step of the

environment.Second, partitioning the action and observation spaces per agent can play a

similar role to the approach of imposing temporal abstractions, which has

been successful in increasing learning efficiency in the single-agent

setting. Relatedly, some of these hierarchical approaches can be

implemented explicitly as multi-agent systems.Finally, good decompositions can also lead to the learning of policies that

are more transferable across different variations of an environment,

i.e., in contrast to a single super-agent that may over-fit to a particular

environment.

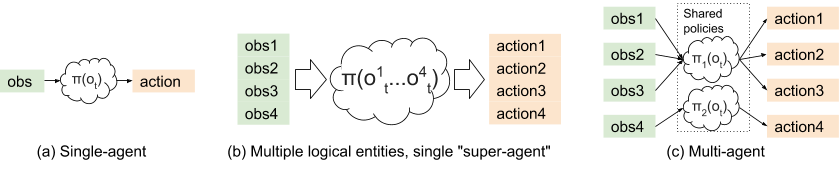

Figure 1: Single-agent approaches (a) and (b) in comparison with

multi-agent RL (c).

Some examples of multi-agent applications include:

Traffic congestion reduction: It turns out that by intelligently

controlling the speed of a few autonomous vehicles we can drastically

increase the traffic flow. Multi-agent can be a requirement here, since in

mixed-autonomy settings, it is unrealistic to model traffic lights and

vehicles as a single agent, which would involve the synchronization of

observations and actions across all agents in a wide area.

Flow simulation, without AVs and then with AV agents (red vehicles):

Antenna tilt control: The joint configuration of cellular base stations

can be optimized according to the distribution of usage and topology of the

local environment. Each base station can be modeled as one of multiple agents

covering a city.

OpenAI Five: Dota 2 AI agents are trained to coordinate with each other to

compete against humans. Each of the five AI players is implemented as a separate

neural network policy and trained together with large-scale PPO.

Introducing multi-agent support in RLlib

In this blog post we introduce general purpose support for multi-agent RL in

RLlib, including compatibility with most of RLlib’s distributed

algorithms: A2C / A3C, PPO, IMPALA, DQN, DDPG, and Ape-X. In the remainder

of this blog post we discuss the challenges of multi-agent RL, show how to train

multi-agent policies with these existing algorithms, and also how to implement

specialized algorithms that can deal with the non-stationarity and increased

variance of multi-agent environments.

There are currently few libraries for multi-agent RL, which increases the

initial overhead of experimenting with multi-agent approaches. Our goal is to

reduce this friction and make it easy to go from single-agent to multi-agent RL

in both research and application.

Why supporting multi-agent is hard

Building software for a rapidly developing field such as RL is challenging,

multi-agent especially so. This is in part due to the breadth of techniques used

to deal with the core issues that arise in multi-agent learning.

Consider one such issue: environment non-stationarity. In the below figure,

the red agent’s goal is to learn how to regulate the speed of the traffic. The

blue agents are also learning, but only to greedily minimize their own travel

time. The red agent may initially achieve its goal by simply driving at the

desired speed. However, in a multi-agent environment, the other agents will

learn over time to meet their own goals – in this case, bypassing the red

agent. This is problematic since from a single-agent view (i.e., that of the red

agent), the blue agents are “part of the environment”. The fact that environment

dynamics are changing from the perspective of a single agent violates the Markov

assumptions required for the convergence of Q-learning algorithms such as

DQN.

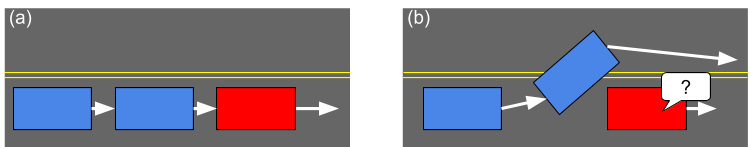

Figure 2: Non-stationarity of environment: Initially (a), the red agent

learns to regulate the speed of the traffic by slowing down. However, over time

the blue agents learn to bypass the red agent (b), rendering the previous

experiences of the red agent invalid.

A number of algorithms have been proposed that help address this issue, e.g.,

LOLA, RIAL, and Q-MIX. At a high level, these algorithms take

into account the actions of the other agents during RL training, usually by

being partially centralized for training, but decentralized during execution.

Implementation wise, this means that the policy networks may have dependencies

on each other, i.e., through a mixing network in Q-MIX:

Figure 3: The Q-mix network architecture, from QMIX: Monotonic Value Function

Factorisation for Deep Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning. Individual

Q-estimates are aggregated by a monotonic mixing network for efficiency of final

action computation.

Similarly, policy-gradient algorithms like A3C and PPO may struggle in

multi-agent settings, as the credit assignment problem becomes increasingly

harder with more agents. Consider a traffic gridlock between many autonomous

agents. It is easy to see that the reward given to an agent – here reflecting

that traffic speed has dropped to zero – will have less and less correlation

with the agent’s actions as the number of agents increases:

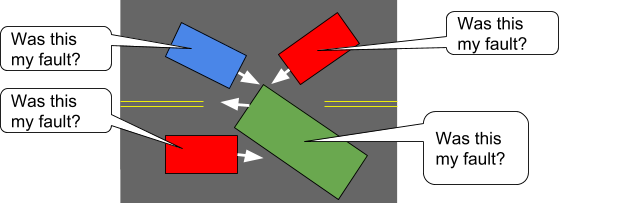

Figure 4: High variance of advantage estimates: In this traffic gridlock

situation, it is unclear which agents’ actions contributed most to the problem

— and when the gridlock is resolved, from any global reward it will be unclear

which agents get credit.

One class of approaches here is to model the effect of other agents on the

environment with centralized value functions (the “Q” boxes in Figure 5)

function, as done in MA-DDPG. Intuitively, the variability of individual

agent advantage estimates can be greatly reduced by taking into account the

actions of other agents:

Figure 5: The MA-DDPG architecture, from Multi-Agent Actor-Critic for Mixed

Cooperative-Competitive Environments. Policies run using only local

information at execution time, but may take advantage of global information at

training time.

So far we’ve seen two different challenges and approaches for tackling

multi-agent RL. That said, in many settings training multi-agent policies

using single-agent RL algorithms can yield surprisingly strong results. For

example, OpenAI Five has been successful using only a combination of large-scale

PPO and a specialized network model. The only considerations for

multi-agent are the annealing of a “team spirit” hyperparameter that influences

the level of shared reward, and a shared “max-pool across Players” operation in

the model to share observational information.

Multi-agent training in RLlib

So how can we handle both these specialized algorithms and also the standard

single-agent RL algorithms in multi-agent settings? Fortunately RLlib’s

design makes this fairly simple. The relevant principles to multi-agent

are as follows:

-

Policies are represented as objects: All gradient-based algorithms in

RLlib declare a policy graph object, which includes a policy model

$pi_theta(o_t)$, a trajectory postprocessing function

$post_theta(traj)$,

and finally a policy loss $L(theta; X)$. This policy graph object

specifies enough for the distributed framework to execute environment rollouts

(by querying $pi_theta$), collate experiences (by applying

$post_theta$), and finally to improve the policy (by descending

$L(theta; X)$). -

Policy objects are black boxes: To support multi-agent, RLlib just needs

to manage the creation and execution of multiple policy graphs per

environment, and add together the losses during policy optimization.

Policy graph objects are treated largely as black boxes by RLlib, which means

that they can be implemented in any framework including TensorFlow and

PyTorch. Moreover, policy graphs can internally share variables and layers

to implement specialized algorithms such as Q-MIX and MA-DDPG, without special

framework support.

To make the application of these principles concrete, In the next few sections

we walk through code examples of using RLlib’s multi-agent APIs to execute

multi-agent training at scale.

Multi-agent environment model

We are not aware of a standard multi-agent environment interface, so we wrote

our own as a straightforward extension of the gym interface. In a

multi-agent environment, there can be multiple acting entities per step. As a

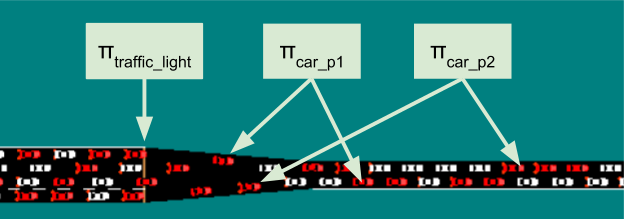

motivating example, consider a traffic control scenario (Figure 6) where

multiple controllable entities (e.g., traffic lights, autonomous vehicles) work

together to reduce highway congestion.

In this scenario,

- Each of these agents can act at different time-scales (i.e., act

asynchronously). - Agents can come and go from the environment as time progresses.

Figure 6. RLlib multi-agent environments can model multiple independent

agents that come and go over time. Different policies can be assigned to agents

as they appear.

This is formalized in the MultiAgentEnv interface, which can returns

observations and rewards from multiple ready agents per step:

# Example: using a multi-agent env

> env = MultiAgentTrafficEnv(num_cars=20, num_traffic_lights=5)

# Observations are a dict mapping agent names to their obs. Not all

# agents need to be present in the dict in each time step.

> print(env.reset())

{

"car_1": [[...]],

"car_2": [[...]],

"traffic_light_1": [[...]],

}

# Actions should be provided for each agent that returned an observation.

> new_obs, rewards, dones, infos = env.step(

actions={"car_1": ..., "car_2": ...})

# Similarly, new_obs, rewards, dones, infos, etc. also become dicts

> print(rewards)

{"car_1": 3, "car_2": -1, "traffic_light_1": 0}

# Individual agents can early exit; env is done when "__all__" = True

> print(dones)

{"car_2": True, "__all__": False}

Any Discrete, Box, Dict, or Tuple observation space from OpenAI gym can be

used for these individual agents, allowing for multiple sensory inputs per

agent (including communication between agents, it desired).

Multiple levels of API support

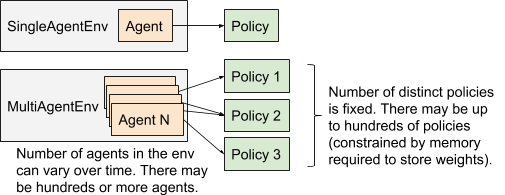

At a high level, RLlib models agents and policies as objects that may be bound

to each other for the duration of an episode (Figure 7). Users can leverage this

abstraction to varying degrees, from just using a single-agent shared policy, to

multiple policies, to fully customized policy optimization:

Figure 7: The multi-agent execution model in RLlib compared with

single-agent execution.

Level 1: Multiple agents, shared policy

If all “agents” in the env are homogeneous (e.g., multiple independent cars in a

traffic simulation), then it is possible to use existing single-agent algorithms

for training. Since there is still only a single policy being trained, RLlib

only needs to internally aggregate the experiences of the different agents prior

to policy optimization. The change is minimal on the user side:

from single-agent:

register_env("your_env", lambda c: YourEnv(...))

trainer = PPOAgent(env="your_env")

while True:

print(trainer.train()) # distributed training step

to multi-agent:

register_env("your_multi_env", lambda c: YourMultiEnv(...))

trainer = PPOAgent(env="your_multi_env")

while True:

print(trainer.train()) # distributed training step

Note that the PPO “Agent” here is a just a naming convention carried over from

the single-agent API. It acts more as a “trainer” of agents than an actual

agent.

Level 2: Multiple agents, multiple policies

To handle multiple policies, this requires the definition of which agent(s) are

handled by each policy. We handle this in RLlib via a policy mapping function,

which assigns agents in the env to a particular policy when the agent first

enters the environment. In the following examples we consider a hierarchical

control setting where supervisor agents assign work to teams of worker agents

they oversee. The desired configuration is to have a single supervisor policy

and an ensemble of two worker policies:

def policy_mapper(agent_id):

if agent_id.startswith("supervisor_"):

return "supervisor_policy"

else:

return random.choice(["worker_p1", "worker_p2"])

In the example, we always bind supervisor agents to the single supervisor

policy, and randomly divide other agents between an ensemble of two different

worker policies. These assignments are done when the agent first enters the

episode, and persist for the duration of the episode. Finally, we need to define

the policy configurations, now that there is more than one. This is done as part

of the top-level agent configuration:

trainer = PPOAgent(env="control_env", config={

"multiagent": {

"policy_mapping_fn": policy_mapper,

"policy_graphs": {

"supervisor_policy":

(PPOPolicyGraph, sup_obs_space, sup_act_space, sup_conf),

"worker_p1": (

(PPOPolicyGraph, work_obs_s, work_act_s, work_p1_conf),

"worker_p2":

(PPOPolicyGraph, work_obs_s, work_act_s, work_p2_conf),

},

"policies_to_train": [

"supervisor_policy", "worker_p1", "worker_p2"],

},

})

while True:

print(trainer.train()) # distributed training step

This would generate a configuration similar to that shown in Figure 2. You can

pass in a custom policy graph class for each policy, as well as different policy

config dicts. This allows for any of RLlib’s support for customization (e.g.,

custom models and preprocessors) to be used per policy, as well as

wholesale definition of a new class of policy.

Advanced examples:

Level 3: Custom training strategies

For advanced applications or research use cases, it is inevitable to run into

the limitations of any framework.

For example, let’s suppose multiple training methods are desired: some agents

will learn with PPO, and others with DQN. This can be done in a way by swapping

weights between two different trainers (there is a code example here), but

this approach won’t scale with even more types of algorithms thrown in, or if

e.g., you want to use experiences to train a model of the environment at the

same time.

In these cases we can fall back to RLlib’s underlying system Ray to

distribute computations as needed. Ray provides two simple parallel primitives:

- Tasks, which are Python functions executed asynchronously via

func.remote() - Actors, which are Python classes created in the cluster via

class.remote(). Actor methods can be called via

actor.method.remote().

RLlib builds on top of Ray tasks and actors to provide a toolkit for distributed

RL training. This includes:

- Policy graphs (as seen in previous examples)

- Policy evaluation: the PolicyEvaluator class manages the environment

interaction loop that generates batches of experiences. When created as

Ray actors, it can be used to gather experiences in a distributed way. - Policy optimization: these implement distributed strategies for

improving policies. You can use one of the existing optimizers or go with a

custom strategy.

For example, you can create policy evaluators to gather multi-agent

rollouts, and then process the batches as needed to improve the policies:

# Initialize a single-node Ray cluster

ray.init()

# Create local instances of your custom policy graphs

sup, w1, w2 = SupervisorPolicy(), WorkerPolicy(), WorkerPolicy()

# Create policy evaluators (Ray actor processes running in the cluster)

evaluators = []

for i in range(16):

ev = PolicyEvaluator.as_remote().remote(

env_creator=lambda ctx: ControlEnv(),

policy_graph={

"supervisor_policy": (SupervisorPolicy, ...),

"worker_p1": ..., ...},

policy_mapping_fn=policy_mapper,

sample_batch_size=500)

evaluators.append(ev)

while True:

# Collect experiences in parallel using the policy evaluators

futures = [ev.sample.remote() for ev in evaluators]

batch = MultiAgentBatch.concat_samples(ray.get(futures))

# >>> print(batch)

# MultiAgentBatch({

# "supervisor_policy": SampleBatch({

# "obs": [[...], ...], "rewards": [0, ...], ...

# }),

# "worker_p1": SampleBatch(...),

# "worker_p2": SampleBatch(...),

# })

your_optimize_func(sup, w1, w2, batch) # Custom policy optimization

# Broadcast new weights and repeat

for ev in evaluators:

ev.set_weights.remote({

"supervisor_policy": sup.get_weights(),

"worker_p1": w1.get_weights(),

"worker_p2": w2.get_weights(),

})

In summary, RLlib provides several levels of APIs targeted at progressively more

requirements for customizability. At the highest levels this provides a simple

“out of the box” training process, but you retain the option to piece together

your own algorithms and training strategies from the core multi-agent

abstractions. To get started, here are a couple intermediate level scripts that

can be run directly: multiagent_cartpole.py,

multiagent_two_trainers.py.

Performance

RLlib is designed to scale to large clusters – and this applies to multi-agent

mode as well – but we also apply optimizations such as vectorization for

single-core efficiency. This allows for effective use of the multi-agent APIs on

small machines.

To show the importance of these optimizations, in the below graph we plot

single-core policy evaluation throughout vs the number of agents in the

environment. For this benchmark the observations are small float vectors, and

the policies are small 16×16 fully connected networks. We assign each agent to a

random policy from a pool of 10 such policy networks. RLlib manages over 70k

actions/s/core at 10000 agents per environment (the bottleneck becomes Python

overhead at this point). When vectorization is turned off, experience collection

slows down by 40x:

We also evaluate the more challenging case of having many distinct policy

networks used in the environment. Here we can still leverage vectorization to

fuse multiple TensorFlow calls into one, obtaining more stable per-core

performance as the number of distinct policies scales from 1 to 50:

Conclusion

This blog post introduces a fast and general framework for multi-agent

reinforcement learning. We’re currently working with early users of this

framework in BAIR, the Berkeley Flow team, and industry to further

improve RLlib. Try it out with 'pip install ray[rllib]' and tell us about

your own use cases!

Documentation for RLlib and multi-agent support can be found at

https://rllib.io.

Erin Grant, Eric Jang, and Eugene Vinitsky provided helpful input for this blog

post.